iMAP State of Internet Censorship Report 2022 - Philippines

In recent years, and with the COVID-19 pandemic increasing people’s reliance on digital technologies and with it the role of ICT regulators, agencies such as the NTC have come under fire for the “politicization” of the country’s telecommunications sector.1 This was most apparent under the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte, whose six-year presidency was marred by the systematic undermining of democratic institutions and countless attacks against critical media and activists.

In June 2022, before Duterte’s term of office ended, the NTC ordered internet service providers to block 26 websites,2 including news sites Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly, allegedly over their ties to “communist-terrorist groups”. The same month, news website Rappler was once again ordered to shut down after the Securities and Exchange Commission upheld its ruling to revoke the media company’s operating licence.

Despite this, OONI network measurement data collected from 23 ISPs confirms the blocking in the Philippines of 16 websites from 1 January 2022 to 30 June 2022. All websites were blocked through DNS hijacking. This number is one of the lowest among the countries covered in the study.

The blocked websites are related to gambling, pornography, anonymization and circumvention tools, social networking, and alternative culture.

No significant censorship was found during the testing of instant messaging apps and circumvention tools, with the exception of Psiphon which recorded high anomalies and should be investigated further.

Table of Contents

Network landscape and internet penetration

Cases of internet censorship and surveillance

Examining internet censorship in the Philippines

Instant messaging and circumvention tools

How are the network measurements gathered?

How are the network measurements analysed?

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

Network landscape and internet penetration

Population: 109 million people3

Internet penetration rate: 72.7% in 20204

Mobile broadband: 149.6 subscriptions in 20205

Fixed-line broadband: 7.9 million subscriptions in 20206

Major ISPs:

Globe: 79.7 million subscribers as of March 20227

PLDT Mobile/Smart: 71.8 million subscribers as of March 20228

Dito: 1 million subscribers as of June 20219

PLDT Home: 2.6 million subscribers as of March 202210

Converge: 1.8 million subscribers as of March 202211 Most ISPs in the Philippines are publicly listed corporations. In March 2022, the government lifted the 40 per cent foreign ownership restriction allowing foreign investors to acquire controlling stakes in Philippine telecommunications and transport companies.12 Singapore state-owned telco Singtel has minority ownership of Globe while Japanese government-linked NTT owns a significant stake in PLDT. China’s state-owned telco China Telecom owns 40 per cent of the newcomer Dito Telecomunnity.

Political landscape

The Philippines’ main regulatory body for the information and communications technology (ICT) industry is the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), established under the Aquino administration in 2016.13 The department serves as the primary policy, planning, coordinating, implementing, and administrative entity of the government’s executive branch in matters related to the national ICT development agenda. The DICT has three attached agencies: the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC), the National Privacy Commission (NPC), and the Cybercrime Investigation and Coordination Center (CICC). The Philippines’ telecommunication regulatory environment, however, falls below international standards.14 resulting in substandard outcomes such as high prices of mobile phone and internet services and low internet quality.15

In recent years, and with the COVID-19 pandemic increasing people’s reliance on digital technologies and with it the role of ICT regulators, agencies such as the NTC have come under fire for the “politicization” of the country’s telecommunications sector.16

This was most apparent under the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte, whose six-year presidency was marred by the systematic undermining of democratic institutions and countless attacks against critical media and activists. Various investigative reports and academic studies have uncovered the existence of state-sponsored troll armies17 polluting online discourse and targeting government critics. News websites and progressive groups critical of the government have been linked to the Philippines’ communist insurgency, endangering the lives of journalists and activists.

One of the biggest blows to press freedom came in 2020, when the country’s largest broadcaster, ABS-CBN, was forced to go off the air after pro-government lawmakers rejected its bid for a renewed franchise.18 The NTC was a key player in the ABS-CBN issue, as it is the regulatory agency that has supervision and control over the country’s telecommunications and broadcasting entities. Exercising its power, the NTC ordered the media giant to halt its television and radio broadcasting operations after its congressional franchise expired19. The move drew criticism, however, as the NTC order was deemed to be politicised amid the long-standing public feud between ABS-CBN and then-president Duterte.20

In June 2022, before Duterte’s term of office ended, the NTC ordered internet service providers to block 26 websites,21 including news sites Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly, allegedly over their ties to “communist-terrorist groups”. The same month, news website Rappler was once again ordered to shut down after the Securities and Exchange Commission upheld its ruling to revoke the media company’s operating licence.

The current hostile attitude towards the press, attacks against critics, and use of disinformation strategies have facilitated a thriving environment for disinformation online. These, along with the complicity of Big Tech platforms, played a significant role in the electoral victory of incumbent president Ferdinand Marcos Jr, son of the late dictator who subjected the Philippines to martial law in the 1970s. Analysts have called the Marcoses’ successful return to power as a victory for disinformation, with historical revisionism as the main narrative perpetuated in online spaces.22 Marcos Jr was formally inaugurated as the 17th President of the Philippines on June 30, 2022, with a six-year term until June 2028.

Legal environment

Freedom of expression

Section 4, Article III of the 1987 Constitution guarantees freedom of speech.23 Under the Duterte administration journalists and activists expressing views critical of the government were at heightened risk of being red-tagged or labelled as sympathisers of the communist insurgency. The National Task Force on Ending Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) is notorious for repeatedly red-tagging activists and government critics both through social media and official pronouncements.24 The practice has resulted in the killings of numerous activists25 while ordinary citizens have also been targeted,26 most notably in April 2021 when organisers of community pantries were linked to rebel groups.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government passed the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act which authorises the president to exercise emergency powers to ensure public order and safety.27 One provision of the law, Section 6(f), drew criticism from rights groups as it penalises individuals or groups creating or spreading “false information” about the health crisis on social media and other platforms.28 Within a month of its implementation, at least 47 people were apprehended for alleged violations.29 The National Bureau of Investigation also issued summons to more than a dozen people for allegedly spreading false information,30 including one who was targeted for his post on the alleged misuse of government funds.

Press freedom

Revised Penal Code

The guarantee for freedom of the press is provided for in the 1987 Constitution. In practice, however, journalists in the Philippines who are critical of politicians often face the threat of criminal defamation in carrying out their work. Libel laws are often used to harass, intimidate, and bully journalists who expose misconduct by public officials. The Revised Penal Code (RPC) provides for a prescription period of one year for libel, which upon conviction may result in imprisonment of up to six years and a fine of up to 6,000 pesos.

Cybercrime Prevention Act

The Cybercrime Prevention Act, passed in 2012, does not specify a prescription period for cyberlibel and since this law imposes a higher penalty for similar convictions than that in the RPC, the Department of Justice has interpreted the prescription period for the offence as 12 years.31 The case of Maria Ressa and Reynaldo Santos Jr of the news website Rappler has become one of the most notable cyberlibel cases in recent years.32 The charge against Ressa, Santos Jr, and Rappler and their subsequent conviction in 2020 drew criticism from local and international human rights organisations.33 Similarly, in June 2022, a public official filed cyberlibel complaints – now dropped – against journalists from seven media outlets that reported on his involvement in a graft complaint.34

Other Instruments

Politicians in the Philippines have also used other regulatory mechanisms to punish media organisations that give them unfavourable coverage. ABS-CBN, a major television and radio network, was forced to shut down in May 2020 after Congress members aligned to then-president Rodrigo Duterte denied the renewal of its broadcasting franchise which the network had held for 25 years.35 In June 2022, just before the end of President Duterte’s term, the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) ordered internet service providers to block 26 websites,36 including news sites Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly, over alleged ties to “communist-terrorist groups”. The same month, Rappler was ordered to shut down after the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) upheld the ruling to revoke the media company’s operating licence37. Similar political interference in the regulation of Philippine broadcasting media has also been reported in the past, most notably the NTC gag order at the height of the ‘Hello, Garci’ scandal in 2005.38

Access to information

Section 7, Article III of the 1987 Constitution recognises “the right of the people to information on matters of public concern”. Section 28, Article II declares that “the state adopts and implements a policy of full public disclosure of all its transactions involving public interest”. Even though the Philippine Congress has yet to pass comprehensive legislation on access to information, these constitutional principles have been the foundation for the right to access information in case law, most notably in the 1989 Supreme Court case of Valmonte v Belmonte.39

Executive Order No 2, s 2016

There have been a number of positive developments towards greater access to information in recent years. In July 2016, President Duterte signed the Freedom of Information Executive Order No 2, s 2016 which provides for the implementation of a freedom of information program within the executive branch under the purview of the Department of Justice and the Office of the Solicitor General. The executive order has had a knock-on effect on local government units across the Philippines with several of them passing their own freedom of information ordinances. The executive order has also renewed the pressure on Congress to pass the freedom of information bill that has been stalled since its earliest version was first tabled in the legislative body in the mid-1990s.40

Privacy

Data Privacy Act 2012

The Data Privacy Act 2012, which provides for the protection of personal data in the Philippines, came into effect in September 2016 after the establishment of the National Privacy Commission (NPC) and the promulgation of implementing rules and regulations of the Act.

The law covers the rights of individuals and the obligations of organisations with regard to the collection, storage, use, disclosure, retention, and disposal of personal data.41 It also sets out penalties for violation of data protection law including fines of 100,000 to 5 million pesos, imprisonment from 6 months to 7 years, and if applicable, disqualification from public office. The law has extraterritorial application when the data subject is a Philippine resident or the data processor is an entity with links to the Philippines.

State surveillance

Section 3, Article II of the 1987 Constitution states that the “privacy of communication and correspondence shall be inviolable except upon lawful order of the court”. Article 23 of the Civil Code states that anyone who “directly or indirectly obstructs, defeats, violates or in any manner impedes or impairs […] privacy of communication and correspondence” of another person shall be liable to damages while article 290 of the Revised Penal Code sets the criminal liability for the unlawful discovery of secrets through the “seizure of correspondence”.

Even though the Anti-Wiretapping Act generally prohibits wiretapping, the law has an exemption for “any peace officer […] authorized by a written order of the Court” to carry out surveillance of citizens42. The Anti-Terrorism Act 2020 provides for the use of surveillance of any kind and by any means in the case of suspected terrorism for up to 60 days, extendable up to 30 days, with a written order of the Court of Appeals43. The Cybercrime Prevention Act 2012 allows authorities to intercept network communications and collect all data except the content and identity of the parties44.

In February 2018, the media reported the British government having sold £150,000 worth of hi-tech surveillance equipment at the height of President Duterte’s war on drugs.45

Pornography

Unlike in its neighbouring countries, pornography is not outlawed in the Philippines. However, article 201 of the Revised Penal Code provides for offences relating to immoral doctrines, obscene publications, and obscene exhibitions.

In recent years, the Philippine government and civil society have worked against commercial sexual exploitation of children including child pornography. Anti-Online Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children (OSAEC) Act, which lapsed into law in July 2022, imposes a set of new duties and obligations on social media platforms, electronic service providers, internet and financial intermediaries to prevent child pornography.46 This is on top of the Anti-Child Pornography Act 2009 which has already defined the offence, set out the punishments for it, and provided for powers of the internet regulator in handling child pornography.47

Cases of internet censorship and surveillance

In June 2022, outgoing National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr. requested the NTC to block access to 28 websites allegedly linked to “communist-terrorist” groups, using the Anti-Terrorism law as a legal basis.48 Among the sites that Esperon requested blocked were those of alternative and independent news organisations Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly, and progressive groups Save Our Schools Network, Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, Pamalakaya Pilipinas, and BAYAN.

In the months leading up to the May 2022 elections, there have been a spate of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against the websites of news outlets, fact-checking websites, and opposition politicians.49 News websites ABS-CBN News, Rappler, and Vera Files reported a string of cyberattacks in December 2021 which coincided with political news coverage,50 and in February 2022 the CNN Philippines website went down while the network was hosting a presidential debate.51 The attacks, which periodically forced the sites offline, escalated in severity in the months leading up to the polls and appeared to be coordinated.52

Examining internet censorship in the Philippines

Findings

As part of this study, network measurements were collected through OONI Probe software tests performed across a total of 23 different ISPs in the Philippines from 1 January 2022 to 30 June 2022.

Blocked websites

Several websites were found to be blocked in the Philippines as part of this study. Analysis of the network measurement data collected through OONI Probe Web Connectivity tests of 2,002 websites performed across 23 ISPs did not find any confirmed blocking of websites by Philippine ISPs. However, heuristic analysis of the measurement data found that 16 websites were blocked by Philippine ISPs through DNS hijacking.

The blocked websites fall under the following categories: gambling, pornography, anonymization and circumvention tools, social networking, and culture.

The table below illustrates the distribution of websites that were confirmed to be blocked in the Philippines by category as part of this study from 1 January 2022 to 30 June 2022.

| Category | Blocked Websites | OONI Probe Measurements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMB | Gambling | 7 | 4,745 |

| PORN | Pornography | 6 | 8,228 |

| ANON | Anonymization and circumvention tools | 1 | 21,975 |

| GRP | Social Networking | 1 | 21,156 |

| CULTR | Culture | 1 | 18,394 |

| NEWS | News Media | – | 54,840 |

| HUMR | Human Rights Issues | – | 33,150 |

| LGBT | LGBT | – | 25,065 |

| COMT | Communication Tools | – | 23,621 |

| HOST | Hosting and Blogging Platforms | – | 19,165 |

| MMED | Media sharing | – | 14,099 |

| REL | Religion | – | 11,593 |

| PUBH | Public Health | – | 10,530 |

| ENV | Environment | – | 8,730 |

| POLR | Political Criticism | – | 8,627 |

| DATE | Online Dating | – | 5,667 |

| SRCH | Search Engines | – | 5,487 |

| FILE | File-sharing | – | 4,926 |

| XED | Sex Education | – | 4,572 |

| GOVT | Government | – | 4,512 |

| HACK | Hacking Tools | – | 4,190 |

| CTRL | Control content | – | 4,128 |

| ALDR | Alcohol & Drugs | – | 3,418 |

| ECON | Economics | – | 2,819 |

| COMM | E-commerce | – | 2,208 |

| GAME | Gaming | – | 2,193 |

| PROV | Provocative Attire | – | 2,096 |

| Aggregate | 16 | 333,328 |

Gambling

Seven gambling websites were found to be blocked in the Philippines during the testing period of 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022. Even though OONI Probe measurements did not find any evidence of a block, it could be confirmed through heuristic analysis.

| Websites | Measured | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| www.pokerstars.com | 128 | 105 (82.03%) | 23 (17.97%) | – |

| www.888casino.com | 131 | 109 (83.21%) | 22 (16.79%) | – |

| www.betfair.com | 130 | 107 (82.31%) | 23 (17.69%) | – |

| www.casino.com | 97 | 96 (98.97%) | 1 (1.03%) | – |

| www.goldenpalace.com | 28 | 18 (64.29%) | 10 (35.71%) | – |

| www.partypoker.com | 128 | 106 (82.81%) | 22 (17.19%) | – |

| www.pokerroom.com | 92 | 90 (97.83%) | 2 (2.17%) | – |

Pornography

Six pornography websites were found to be blocked in the Philippines during the testing period of 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022. All were confirmed blocked through heuristic analysis as the OONI Probe measurements did not return any evidence of a block.

| Websites | Measured | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| deviantclip.com | 130 | 108 (83.08%) | 22 (16.92%) | – |

| jizzhut.com | 130 | 112 (86.15%) | 18 (13.85%) | – |

| motherless.com | 130 | 102 (78.46%) | 28 (21.54%) | – |

| porn.com | 130 | 109 (83.85%) | 21 (16.15%) | – |

| xhamster.com | 134 | 109 (81.34%) | 25 (18.66%) | – |

| xnxx.com | 132 | 105 (79.55%) | 27 (20.45%) | – |

Anonymization and circumvention tools

Only one website that provides anonymization and circumvention tools was blocked in the Philippines during the testing period of 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022. This website helps internet users anonymize the HTTP referer of the URLs that they visit online. The blocking was confirmed through heuristic analysis rather than OONI Probe measurement data.

| Websites | Measured | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| anonym.to | 211 | 168 (79.62%) | 39 (18.48%) | 4 (1.9%) |

Social networking

Only one social networking website was confirmed blocked in the Philippines during the testing period from 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022. The website provides analytics of trending topics on Twitter. Even though OONI Probe measurements did not return any evidence of a block, the heuristic analysis performed could confirm blocking.

| Websites | Measured | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| www.trendsmap.com | 262 | 225 (85.88%) | 36 (13.74%) | 1 (0.38%) |

Culture

Only one website that fall in the culture category was found to be blocked in the Philippines during the testing period of 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022. The blocking was confirmed through heuristic analysis as the OONI Probe measurement data did not find any evidence of a block. The blocked website hosts erotic literature contributed by its users.

| Websites | Measured | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| www.asstr.org | 143 | 121 (84.62%) | 22 (15.38%) | – |

Instant messaging and circumvention tools

The OONI Probe measurements examining the reachability of instant messaging services and circumvention tools did not find any evidence of network tempering of Facebook Messenger, Telegram, Signal, WhatsApp, Psiphon, and Tor throughout the testing period. However, the Psiphon test found a significant level of anomalies (over 97 per cent) during the testing period which should be investigated further to rule out any network tempering in the Philippines.

| Tests | Measured | Blocked | Not Blocked | Anomalous | Failed | ISPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facebook Messenger | 5,169 | – | 5,142 (99.48%) | 18 (0.35%) | 9 (0.17%) | 21 |

| Telegram | 5,180 | – | 5,134 (99.11%) | 37 (0.71%) | 9 (0.17%) | 21 |

| Signal | 5,145 | – | 4,946 (96.13%) | 192 (3.73%) | 7 (0.14%) | 21 |

| 5,159 | – | 5,071 (98.29%) | 35 (0.68%) | 53 (1.03%) | 21 | |

| Psiphon | 5,241 | – | 127 (2.42%) | 5,091 (97.14%) | 23 (0.44%) | 23 |

| Tor | 5,181 | – | 5,171 (99.81%) | 10 (0.19%) | – | 23 |

| Tor Snowflake | 120 | – | 107 (89.17%) | 13 (10.83%) | – | 14 |

Acknowledgement of limitations

| January | February | March | April | May | June | Aggregate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | 68,467 | 44,902 | 72,351 | 60,839 | 68,148 | 75,539 | 390,246 |

| Hostnames | 1,856 | 1,861 | 1,810 | 1,759 | 1,742 | 1,759 | 2,002 |

| ASNs | 13 | 12 | 12 | 19 | 11 | 10 | 23 |

Summary of OONI Probe Web Connectivity measurement data for the Philippines from 1 January until 30 June 2022

During the testing period from 1 January 2022 until 30 June 2022, more than 390,000 web connectivity measurements in the Philippines were collected using the OONI Probe. The web connectivity measurements could not confirm any blocking by ISPs. However, a number of blocked websites could be confirmed through heuristic analysis.

Another limitation of this study is the number and types of websites included in the OONI Probe measurements. A total of 2,002 websites were tested during the six-month period but the number of different websites tested varies when compared month-to-month ranging from 1,742 to 1,861 websites. While the low variance indicates a good coverage of websites tested across the testing period, a number of limitations should be taken into account.

The global and country test lists contain a very small sample of URLs that may be visited by Philippine internet users. Testing web connectivity using the test lists is thus not representative of the whole internet in the Philippines. Some URLs included in the test lists could be outdated, miscategorised, or belonged to multiple categories which may have resulted in skewed or varying interpretations of the measurement data.

The measurements collected are also limited by the number of different ISPs covered. In any given month, only 10 to 19 different ISPs are included in the measurement data as compared to 23 different ISPs covered for the whole testing period. The high variance between these figures indicates less than ideal ISP coverage of the measurement data. There may be Philippine ISPs not included in some measurements that would return confirmed blocking and thus limit the data analysis.

Despite these limitations, the measurement data from OONI Probe is useful in providing a broad indication of the general depth and breadth of internet censorship in the Philippines. Similar studies in the future may overcome some of these limitations by deploying OONI Probe on more devices, running a consistent number of tests periodically, and having wider coverage of ISPs across the Philippines.

Conclusion

During the reporting period, the Philippine government utilized a wide range of laws as grounds to restrict freedom of expression and opinion online. Media organizations critical of the Philippine government are consistently at the receiving end of these tactics, which have become commonplace under the term of former President Duterte. The use of cybercrime prevention and anti-terrorism laws to harass, intimidate, and bully Philippine journalists exacerbates the already hostile environment for the press, mired with violent practices like red tagging, enforced disappearance, and extrajudicial killings of media practitioners.

Specific to internet censorship, all 16 of the blocked websites were confirmed through further heuristic analysis based on measurements collected through OONI Probe. A comprehensive review of the country test list used in OONI Probe measurements could potentially improve the detection of network interference in the Philippines.

Further investigation is especially needed in anticipation of President Marcos Jr’s expected continuation of his predecessor’s censorship tactics and hardline stance against critics. Marcos’ camp, even before assuming the presidency, has already shunned and harassed journalists, favouring the influencers and vloggers who helped catapult him into power.

The internet remains relatively free and open in the Philippines as compared to other countries in Southeast Asia. But judging by current trends, laws and institutions will continue to be used to justify the censorship of critical voices both online and offline, all towards the President’s “call for unity” in the country and among Filipinos.53

Annex PH-1: Probed ISPs

Probed ISPs: Angeles City Cable Television Network, Inc. (AS137226), Asian Vision Cable (AS56099), CMD Cable Vision, Inc (AS140243), Converge ICT Solutions Inc. (AS17639), Dasca Cable Services, Inc. (AS136515), DCTV Cable Network Broadband Services Inc (AS133334), Dito Telecommunity Corp. (AS139831), Eastern Telecoms Phils., Inc. (AS9658), Galaxy Cable Corp. (AS135582), Globe Telecom Inc. (AS132199), Globe Telecoms (AS4775), Globotech Communications (AS36666), Google LLC (AS36384), Infinivan Incorporated (AS135607), Kabayan Cable TV Systems Inc. (AS135594), M247 Europe Srl (AS9009), Nexlogic Telecommunications Network, Inc. (AS135025), Philcomm (AS9927), Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (AS9299), RBC Cable Master System (AS138025), Skybroadband Skycable Corporation (AS23944), Smart Broadband, Inc. (AS10139), and Zenlayer Inc (AS21859)

Annex I: Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| DNS | DNS stands for “Domain Name System” and it maps domain names to IP addresses. A domain is a name that is commonly attributed to websites (when they’re created), so that they can be more easily accessed and remembered. For example, twitter.com is the domain of the Twitter website. However, computers can’t connect to internet services through domain names, but based on IP addresses: the digital address of each service on the internet. Similarly, in the physical world, you would need the address of a house (rather than the name of the house itself) in order to visit it. The Domain Name System (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a human- readable domain name (such as ooni.org) into its numerical IP address counterpart (in this case:104.198.14.52), thus allowing your computer to access the intended website. |

| HTTP | The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the underlying protocol used by the World Wide Web to transfer or exchange data across the internet. The HTTP protocol allows communication between a client and a server. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a server, and the server’s response to the client’s request. All websites include an HTTP (or HTTPS) prefix (such as http://example.com/) so that your computer (the client) can request and receive the content of a website (hosted on a server). All websites include an HTTP (or HTTPS) prefix (such as http://example.com/) so that your computer (the client) can request and receive the content of a website (hosted on a server). The transmission of data over the HTTP protocol is unencrypted. |

| ISP | An Internet Service Provider (ISP) is an organization that provides services for accessing and using the internet. ISPs can be state-owned, commercial, community-owned, non-profit, or otherwise privately owned. Vodafone, AT&T, Airtel, and MTN are examples of ISPs. |

| Middle boxes | A middlebox is a computer networking device that transforms, inspects, filters, or otherwise manipulates traffic for purposes other than packet forwarding. Many Internet Service Providers (ISPs) around the world use middleboxes to improve network performance, provide users with faster access to websites, and for a number of other networking purposes. Sometimes though, middleboxes are also used to implement internet censorship and/or surveillance. The OONI Probe app includes two tests designed to measure networks with the aim of identifying the presence of middleboxes. |

| TCP | The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is one of the main protocols on the internet. To connect to a website, your computer needs to establish a TCP connection to the address of that website. TCP works on top of the Internet Protocol (IP), which defines how to address computers on the internet. When speaking to a machine over the TCP protocol you use an IP and port pair, which looks something like this: 10.20.1.1:8080. The main difference between TCP and (another very popular protocol called) UDP is that TCP has the notion of a “connection”, making it a “reliable” transport protocol. |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security (TLS) – also referred to as “SSL” – is a cryptographic protocol that allows you to maintain a secure, encrypted connection between your computer and an internet service. When you connect to a website through TLS, the address of the website will begin with HTTPS (such as https://www.facebook.com/), instead of HTTP. |

A comprehensive glossary related to OONI can be accessed here: https://ooni.org/support/glossary/.

Annex II: Methodology

Data

Data computed based on the heuristics for this report can be downloaded here: https://github.com/Sinar/imap-data whereas aggregated data can be downloaded from OONI Explorer.

Coverage

The iMAP State of Internet Censorship Country Report covers the findings of network measurement collected through Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) OONI Probe App that measures the blocking of websites, instant messaging apps, circumvention tools and network tampering. The findings highlight the websites, instant messaging apps and circumvention tools confirmed to be blocked, the ASNs with censorship detected and method of network interference applied. The report also provides background context on the network landscape combined with the latest legal, social and political issues and events which might have an effect on the implementation of internet censorship in the country.

In terms of timeline, this first iMAP report covers measurements obtained in the six-month period from 1 January 2022 to 30 June 2022. The countries covered in this round are Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. India will only be included starting in the next period of reporting.

How are the network measurements gathered?

Network measurements are gathered through the use of OONI Probe app, a free software tool developed by Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). To learn more about how the OONI Probe test works, please visit https://ooni.org/nettest/.

iMAP Country Researchers and anonymous volunteers run OONI Probe app to examine the accessibility of websites included in the Citizen Lab test lists. iMAP Country Researchers actively review the country-specific test lists to ensure up-to-date websites are included and context-relevant websites are properly categorised, in consultation with local communities and digital rights network partners. We adopt the approach taken by Netalitica in reviewing country-specific test lists.

It is important to note that the findings are only applicable to the websites that were examined and do not fully reflect all instances of censorship that might have occurred during the testing period.

How are the network measurements analysed?

OONI processes the following types of data through its data pipeline: https://github.com/ooni/pipeline.

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from which the user is running OONI Probe tests from, by automatically searching for it based on the user’s IP address through their ASN database the MaxMind GeoIP database.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) of the network used to run OONI Probe app, thereby revealing the network provider of a user.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run to evaluate when network interferences occur and to allow comparison across time. UTC is used as the standard time zone in the time and date information. In addition, the charts generated on OONI MAT will exclude measurements on the last day by default.

Categories

The 32 website categories are based on the Citizenlab test lists: https://github.com/citizenlab/test-lists. As not all websites tested on OONI are on these test lists, these websites would have unclassified categories.

| No. | Category Description | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alcohol & Drugs | ALDR | Sites devoted to the use, paraphernalia, and sale of drugs and alcohol irrespective of the local legality. |

| 2 | Religion | REL | Sites devoted to discussion of religious issues, both supportive and critical, as well as discussion of minority religious groups. |

| 3 | Pornography | PORN | Hard-core and soft-core pornography. |

| 4 | Provocative Attire | PROV | Websites which show provocative attire and portray women in a sexual manner, wearing minimal clothing. |

| 5 | Political Criticism | POLR | Content that offers critical political viewpoints. Includes critical authors and bloggers, as well as oppositional political organizations. Includes pro-democracy content, anti-corruption content as well as content calling for changes in leadership, governance issues, legal reform. Etc. |

| 6 | Human Rights Issues | HUMR | Sites dedicated to discussing human rights issues in various forms. Includes women's rights and rights of minority ethnic groups. |

| 7 | Environment | ENV | Pollution, international environmental treaties, deforestation, environmental justice, disasters, etc. |

| 8 | Terrorism and Militants | MILX | Sites promoting terrorism, violent militant or separatist movements. |

| 9 | Hate Speech | HATE | Content that disparages particular groups or persons based on race, sex, sexuality or other characteristics |

| 10 | News Media | NEWS | This category includes major news outlets (BBC, CNN, etc.) as well as regional news outlets and independent media. |

| 11 | Sex Education | XED | Includes contraception, abstinence, STDs, healthy sexuality, teen pregnancy, rape prevention, abortion, sexual rights, and sexual health services. |

| 12 | Public Health | PUBH | HIV, SARS, bird flu, centers for disease control, World Health Organization, etc |

| 13 | Gambling | GMB | Online gambling sites. Includes casino games, sports betting, etc. |

| 14 | Anonymization and circumvention tools | ANON | Sites that provide tools used for anonymization, circumvention, proxy-services and encryption. |

| 15 | Online Dating | DATE | Online dating services which can be used to meet people, post profiles, chat, etc |

| 16 | Social Networking | GRP | Social networking tools and platforms. |

| 17 | LGBT | LGBT | A range of gay-lesbian-bisexual-transgender queer issues. (Excluding pornography) |

| 18 | File-sharing | FILE | Sites and tools used to share files, including cloud-based file storage, torrents and P2P file-sharing tools. |

| 19 | Hacking Tools | HACK | Sites dedicated to computer security, including news and tools. Includes malicious and non-malicious content. |

| 20 | Communication Tools | COMT | Sites and tools for individual and group communications. Includes webmail, VoIP, instant messaging, chat and mobile messaging applications. |

| 21 | Media sharing | MMED | Video, audio or photo sharing platforms. |

| 22 | Hosting and Blogging Platforms | HOST | Web hosting services, blogging and other online publishing platforms. |

| 23 | Search Engines | SRCH | Search engines and portals. |

| 24 | Gaming | GAME | Online games and gaming platforms, excluding gambling sites. |

| 25 | Culture | CULTR | Content relating to entertainment, history, literature, music, film, books, satire and humour |

| 26 | Economics | ECON | General economic development and poverty related topics, agencies and funding opportunities |

| 27 | Government | GOVT | Government-run websites, including military sites. |

| 28 | E-commerce | COMM | Websites of commercial services and products. |

| 29 | Control content | CTRL | Benign or innocuous content used as a control. |

| 30 | Intergovernmental Organizations | IGO | Websites of intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations. |

| 31 | Miscellaneous content | MISC | Sites that don't fit in any category (XXX Things in here should be categorised) |

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not collect or store users’ IP addresses deliberately. OONI takes measures to remove them from the collected measurements, to protect its users from potential risks. However, there may be instances where users’ IP addresses and other potentially personally-identifiable information are unintentionally collected, if such information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of measurements. For example, this can occur if the tested websites include tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s network location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed through its git repository, and details about what collected network measurements entail can be viewed through OONI Explorer or through OONI’s measurement API.

In order to derive meaning from the measurements collected, OONI processes the data types mentioned above to answer the following questions:

- Which types of OONI tests were run?

- In which countries were those tests run?

- In which networks were those tests run?

- When were tests run?

- What types of network interference occurred?

- In which countries did network interference occur?

- In which networks did network interference occur?

- When did network interference occur?

- How did network interference occur?

To answer such questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to answer such questions by processing network measurements data to enable the following:

- Attributing measurements to a specific country.

- Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

- Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were run for their collection.

- Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the latter indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

- Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

- Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for HTTP blocking.

- Identifying the presence of “middle boxes” within tested networks.

According to OONI, false positives may occur within the processed data due to a number of reasons. DNS resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. While this may appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done with the intention of providing users with faster access to websites. Similarly, false positives may emerge when tested websites serve different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered with.

Furthermore, measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might actually be due to temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not conclusively be a sign of network interference. It is therefore important to test the same sets of websites across time and to cross-correlate data, prior to reaching a conclusion on whether websites are in fact being blocked.

Since block pages differ from country to country and sometimes even from network to network, it is quite challenging to accurately identify them. OONI uses a series of heuristics to try to guess if the page in question differs from the expected control, but these heuristics can often result in false positives. For this reason OONI only says that there is a confirmed instance of blocking when a block page is detected.

Upon collection of more network measurements, OONI continues to develop its data analysis heuristics, based on which it attempts to accurately identify censorship events.

The full list of country-specific test lists containing confirmed blocked websites in Myanmar, Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam can be viewed here: https://github.com/citizenlab/test-lists.

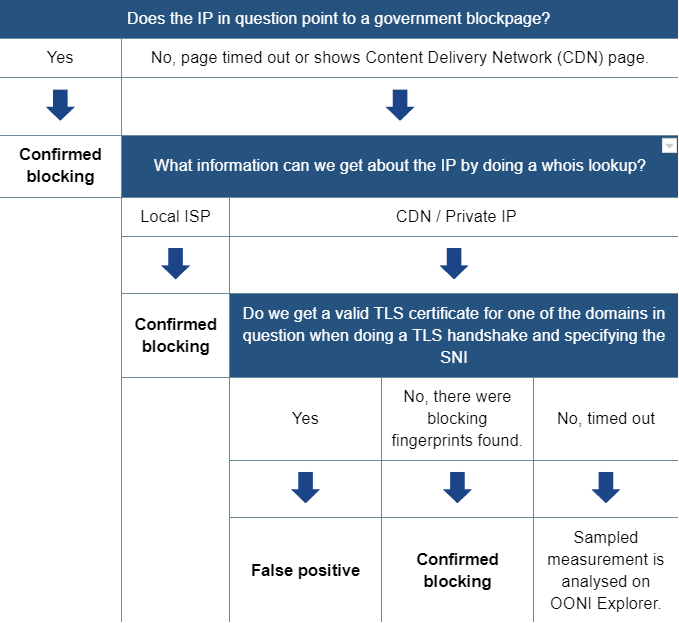

Confirmed vs Heuristics

Confirmed OONI measurements were based on blockpages with fingerprints recorded here https://github.com/ooni/blocking-fingerprints.

Hence, heuristics as below were run on raw measurements on all countries under iMAP to further confirm blockings.

Firstly, IP addresses with more than 10 domains were identified. Then each of the IP address was checked for the following:

When blocking is determined, any domain redirected to these IP addresses would be marked as ‘dns.confirmed’.

Secondly, HTTP titles and bodies were analysed to determine blockpages. This example shows that the HTTP returns the text ‘The URL has been blocked as per the instructions of the DoT in compliance to the orders of Court of Law’. Any domain redirected to these HTTP titles and bodies would be marked as ‘http.confirmed’.

As a result, false positives are eliminated and more confirmed blockings were obtained including countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Philippines which have no confirmed blocking fingerprints on OONI.

In the case of Hong Kong, the results of the heuristics showed external censorship from outside of the country instead of local censorship. Thus, the local researchers had analysed the OONI measurements manually to identify confirmed blockings. The domains identified were based on the timed-out instances.

About iMAP

Internet Monitoring Action Project (iMAP) aims to establish regional and in-country networks that monitor network interference and restrictions to the freedom of expression online in 9 countries: Myanmar, Cambodia, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. Sinar Project is currently working with national digital rights partners in these 9 countries. The project is done via Open Observatory Network Interference (OONI) detection and reporting systems, involving the maintenance of test lists and measurements.

More information available at: imap.sinarproject.org. Any enquiries and suggestions about this report can be directed to team@sinarproject.org.

About Sinar Project

Sinar Project is a civic tech initiative using open technology, open data and policy analysis to systematically make important information public and more accessible to the Malaysian people. It aims to improve governance and encourage greater citizen involvement in the public affairs of the nation by making Parliament and Malaysian Government more open, transparent and accountable. More information available at: https://sinarproject.org.

About EngageMedia

EngageMedia is a nonprofit that promotes digital rights, open and secure technology, and social issue documentary. Combining video, technology, knowledge, and networks, we support Asia-Pacific and global changemakers advocating for human rights, democracy, and the environment. In collaboration with diverse networks and communities, we defend and advance digital rights. Learn more about EngageMedia at https://engagemedia.org.

Balinbin, A. L. (2020, July 8). Politicized media shutdown to drive away investors, says Fitch Solutions. BusinessWorld. https://www.bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2020/07/09/304153/politicized-media-shutdown-to-drive-away-investors-says-fitch-solutions/ ↩︎

NTC orders block to access of websites of CPP-NPA, alternative media, progressive groups. (2022, June 22). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/22/NSA-Esperon-website-block-CPP-NPA-media-groups.html ↩︎

Mapa, D. S. (2021, July 7). 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Population Counts Declared Official by the President [Review of 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Population Counts Declared Official by the President]. Psa.gov.ph; Philippine Statistics Authority. https:///content/2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph-population-counts-declared-official-president ↩︎

Internet user penetration in the Philippines from 2017 to 2020 with forecasts until 2026. (2021, December 13). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/975072/internet-penetration-rate-in-the-philippines/ ↩︎

Mobile cellular subscriptions - Philippines. (n.d.). World Bank Open Data; The World Bank Group. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS?locations=PH ↩︎

Fixed broadband subscriptions - Philippines. (n.d.). World Bank Open Data; The World Bank Group. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS?locations=PH ↩︎

Rey, A. (2021, July 22). Telcos expect at least 1 million subscribers to move networks. RAPPLER. https://www.rappler.com/business/telecommunications-companies-expect-million-subscribers-move-networks/ ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Cordero, T. (2022, May 25). PLDT Home eyes over 1M new fiber subscribers by end-2022. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/money/companies/832861/pldt-home-eyes-over-1m-new-fiber-subscribers-by-end-2022/story/ ↩︎

Converge sustains subscriber growth with revenues up 40% in Q1 2022. (2022, May 16). Converge; Converge ICT Solutions. https://corporate.convergeict.com/news/converge-sustains-subscriber-growth-with-revenues-up-40-in-q1-2022/ ↩︎

Venzon, C. (2022, March 22). Philippines allows foreigners to own telcos, airlines and railways. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Philippines-allows-foreigners-to-own-telcos-airlines-and-railways ↩︎

Tordecilla, K. (2016, May 23). Aquino signs law creating information, communications technology department. CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2016/05/23/Benigno-Aquino-III-DICT-Department-of-Information-and-Communications-Technology.html ↩︎

Gov’t think tank: PH telco regulatory environment weak. (2017, May 31). SunStar. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/145081/govt-think-tank-ph-telco-regulatory-environment-weak ↩︎

Fostering Competition in the Philippines: The Challenge of Restrictive Regulations. (2018). The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/478061551366290646/pdf/Fostering-Competition-in-the-Philippines-The-Challenge-of-Restrictive-Regulations.pdf ↩︎

Balinbin, A. L. (2020, July 8). Politicized media shutdown to drive away investors, says Fitch Solutions. BusinessWorld. https://www.bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2020/07/09/304153/politicized-media-shutdown-to-drive-away-investors-says-fitch-solutions/ ↩︎

Curato, N., Ong, J. C., & Tapsell, R. (2019, August 9). The changing face of fake news. New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/disinformation/ ↩︎

Duterte’s congressional supporters seal Philippine network’s fate | RSF. (2022, July 10). Rsf.org; Reporters Without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/duterte-s-congressional-supporters-seal-philippine-network-s-fate ↩︎

Rivas, R. (2020, May 5). NTC orders ABS-CBN to stop operations. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/259974-ntc-orders-abs-cbn-stop-operations-may-5-2020/ ↩︎

Duterte won’t allow ABS-CBN to operate even if it gets new franchise. (2021, February 8). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2021/2/8/duterte-abs-cbn-franchise-license-to-operate.html ↩︎

NTC orders block to access of websites of CPP-NPA, alternative media, progressive groups. (2022, June 22). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/22/NSA-Esperon-website-block-CPP-NPA-media-groups.html ↩︎

Salazar, C. (2022, May 8). Marcos leads presidential race amid massive disinformation. Pcij.org; Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. https://pcij.org/article/8370/marcos-presidential-elections-massive-disinformation ↩︎

The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, article III, section 4 (1987). https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/ ↩︎

Ranada, P. (2020, September 9). Lorraine Badoy’s red-tagging causes suspension of PCOO 2021 budget hearing. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/lorraine-badoy-red-tagging-causes-suspension-of-pcoo-2021-budget-hearing/ ↩︎

Philippines: End Deadly “Red-Tagging” of Activists. (2022, January 17). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/17/philippines-end-deadly-red-tagging-activists ↩︎

Maginhawa community pantry halts operations due to “red-tagging.” (2021, April 20). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2021/4/20/Maginhawa-community-pantry-halts-operations-red-tagging.html ↩︎

Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, (2022). https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2020/03/24/republic-act-no-11469/ ↩︎

Patag, K. J. (2020, March 25). During state of emergency, “Bayanihan” Act allows imprisonment for “false information.” Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2020/03/25/2003374/during-state-emergency-bayanihan-act-allows-imprisonment-false-information ↩︎

Joaquin, J. J. B., & Biana, H. T. (2020). Philippine crimes of dissent: Free speech in the time of COVID-19. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, 17(1), 174165902094618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659020946181 ↩︎

Torres-Tupas, T. (2020, April 2). NBI summons “more than a dozen” people over COVID-19 social media posts. Inquirer.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1252807/nbi-summons-more-than-a-dozen-people-over-covid-19-social-media-posts ↩︎

Buan, L. (2019, February 14). DOJ: You can be sued for cyber libel within 12 years of publication. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/223517-doj-says-people-can-be-sued-cyber-libel-12-years-after-publication/ ↩︎

Ratcliffe, R. (2020, June 15). Journalist Maria Ressa found guilty of “cyberlibel” in Philippines. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/15/maria-ressa-rappler-editor-found-guilty-of-cyber-libel-charges-in-philippines ↩︎

Regencia, T. (2020, June 15). Maria Ressa found guilty in blow to Philippines’ press freedom. Www.aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/15/maria-ressa-found-guilty-in-blow-to-philippines-press-freedom ↩︎

Cusi drops libel case vs. news orgs, journalists. (2022, June 24). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/24/Cusi-drops-libel-case.html ↩︎

Reporters Without Borders. (2020, July 10). Duterte’s congressional supporters seal Philippine network’s fate. Rsf.org. https://rsf.org/en/duterte-s-congressional-supporters-seal-philippine-network-s-fate ↩︎

NTC orders block to access of websites of CPP-NPA, alternative media, progressive groups. (2022, June 22). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/22/NSA-Esperon-website-block-CPP-NPA-media-groups.html ↩︎

TIMELINE: Rappler-SEC case. (2022, June 30). CNN Philippines. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/30/Rappler-SEC-case-timeline.html ↩︎

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). (2005, June 17). Anti-wiretapping law gags Filipino journalists, says IFJ. IFEX. https://ifex.org/anti-wiretapping-law-gags-filipino-journalists-says-ifj/ ↩︎

Ricardo Valmonte & others v Feliciano Belmonte, Jr., (Supreme Court February 13, 1989). https://lawphil.net/judjuris/juri1989/feb1989/gr_74930_1989.html ↩︎

Gita-Carlos, R. A. (2022, April 2). Pass FOI bill now, Palace urges Congress. Philippine News Agency. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1171276 ↩︎

Data Privacy Act, (2012). https://www.privacy.gov.ph/data-privacy-act/ ↩︎

An Act to Prohibit and Penalize Wire Tapping and Other Related Violations of the Privacy of Communication, and for Other Purposes, (1965). https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1965/ra_4200_1965.html ↩︎

Anti-Terrorism Act, (2020). https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2020/07/03/republic-act-no-11479/ ↩︎

Cybercrime Prevention Act, (2011). https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2012/09/12/republic-act-no-10175/ ↩︎

Ellis-Petersen, H. (2018, February 21). Britain sold spying gear to Philippines despite Duterte’s brutal drugs war. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/21/britain-sold-spying-gear-to-philippines-despite-dutertes-brutal-drugs-war ↩︎

Moaje, M. (2022, August 4). Internet now safer for kids with anti-online sexual abuse law. Philippine News Agency. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1180657 ↩︎

Anti-Child Pornography Act, (2009). https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2009/ra_9775_2009.html ↩︎

Buan, L. (2022, June 22). Esperon uses anti-terror law to block websites including news site. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/esperon-uses-anti-terror-law-block-access-progressive-websites-including-news-organization/ ↩︎

Guest, P. (2022, April 26). “It’s like being under siege”: How DDoS became a censorship tool. Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2022/blackouts-ddos/ ↩︎

Three Philippine media outlets face latest in a string of cyberattacks. (2022, February 1). Committee to Protect Journalists. https://cpj.org/2022/02/three-philippine-media-outlets-string-of-cyberattacks/ ↩︎

Philippines: CNN Philippines hit by cyberattack during presidential debate. (2022, March 4). International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/press-releases/article/philippines-cnn-philippines-hit-by-cyberattack-during-presidential-debate.html ↩︎

Mendoza, G. B. (2021, December 24). Heightened DDoS attacks target critical media. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/technology/cyberattacks-abs-cbn-rappler-vera-files-similar-signatures/ ↩︎

Marcos, F. R. (2022, June 30). Inaugural Address of President Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos, Jr., June 30, 2022. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2022/06/30/inaugural-address-of-president-ferdinand-romualdez-marcos-jr-june-30-2022/ ↩︎