The Longest Silence: Internet Shutdowns During Bangladesh’s 2024 Uprising

This study was conducted by Digitally Right in collaboration with the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). Key contributors include Tohidul Islam Raso from Digitally Right and Maria Xynou from OONI. Suhadha Afrin, a Tech Policy Fellow at Digitally Right and journalist at Prothom Alo, also contributed to the research and documentation for this report. The research has been reviewed by Miraj Ahmed Chowdhury from Digitally Right.

We are equally grateful to Digitally Right’s Network Measurement Fellows across Bangladesh, whose work in tracking disruptions and documenting censorship during the protests helped verify and strengthen the findings of this report. We also thank the journalists whose extensive coverage of the shutdowns provided a vital foundation for this report and the individuals affiliated with operators and service provider organizations who provided interviews and shared relevant information that informed this analysis.

We hope this report contributes to a clearer understanding of the July–August 2024 internet shutdowns in Bangladesh and serves as a foundation for future research into network disruptions and digital rights in Bangladesh.

Download in PDFExecutive Summary

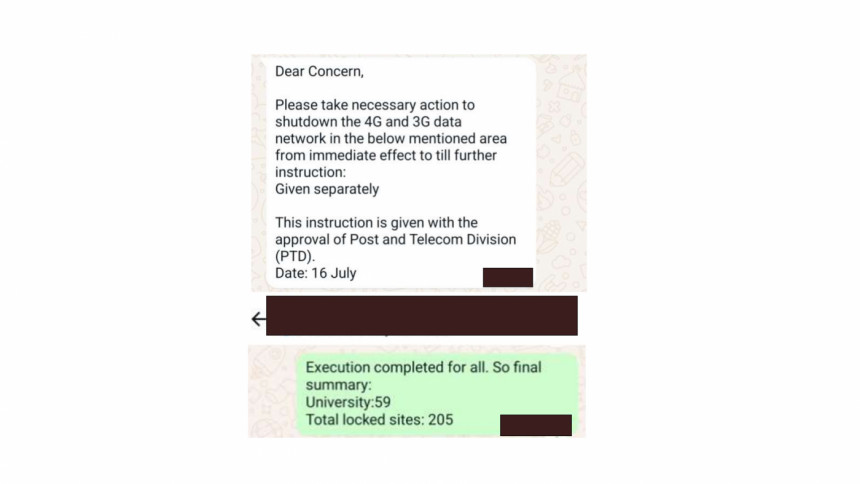

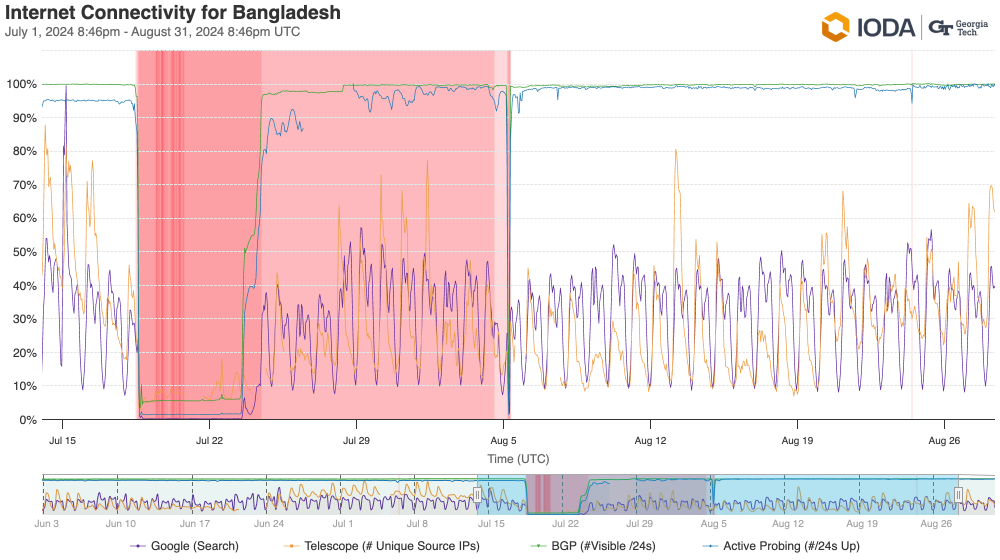

Bangladesh witnessed its worst internet shutdown during the July–August 2024 student-led uprising, which ultimately led to the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government. Over a 22-day period, from mid-July to early August, the shutdowns coincided with mass protests, the killing of hundreds of demonstrators, and widespread human rights violations, as documented by domestic and international observers, including United Nations reports.

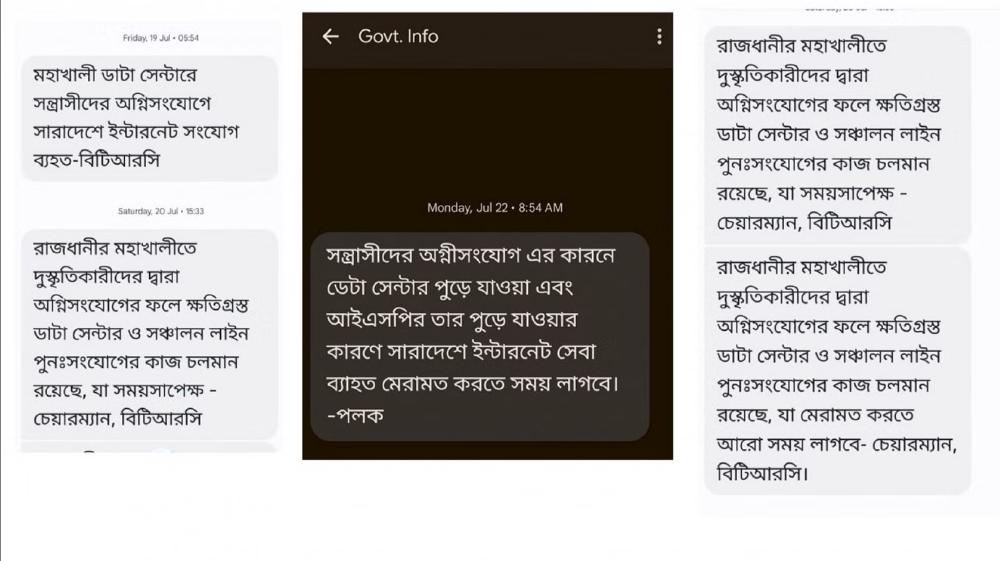

The scale and complexity of the shutdown were unprecedented. Multiple layers of control were deployed, ranging from nationwide blackouts to bandwidth throttling, cache server deactivations, and targeted blocking of social media and VPNs. Implementation was marked by a lack of transparency, overlapping government actors, and informal or verbal directives, leading to conflicting narratives and limited public disclosure.

Yet, this shutdown became one of the most extensively documented in Bangladesh’s history. Local and national media covered nearly every disruption, activists used open-source tools to track and document censorship, and international watchdogs monitored the incidents offering technical data and evidence.

Digitally Right Limited, in collaboration with the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), developed this report to reconstruct a verified timeline of these events, map how the shutdown was enforced at different network layers, and assess its broader implications for accountability, rights, and access to information during political crises.

Key findings include:

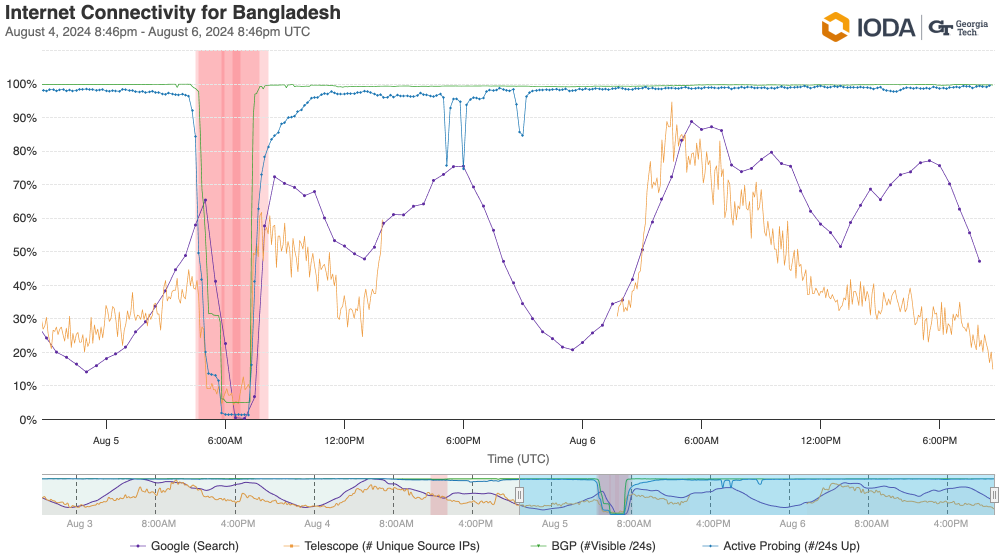

- Unprecedented scale and duration: The shutdown with two full national blackouts (July 18-23 and August 5), bandwidth throttling and targeted blocking was the longest and most geographically widespread in Bangladesh’s history.

- Network disruption aligned with political escalation: The most severe disruptions, including the five-day blackout and the August 5 blackout, broadly coincided with the deadliest phases of unrest. Between July 18-23 alone, media reports documented at least 143 deaths, while August 4-5 saw 223 more, highlighting how shutdowns paralleled spikes in violence.

- Multi-layered methods of control: The state employed diverse tactics, from complete shutdowns of mobile and broadband services to throttling, cache server shutdowns, and selective blocking of social media, messaging apps, and circumvention tools.

- Opacity and fragmented authority: Most measures were ordered informally, often via WhatsApp, with overlapping roles played by the ministry of ICT, BTRC, NTMC, and Department of Telecommunications. Conflicting public statements and a lack of formal orders left citizens and journalists unable to verify or challenge restrictions in real time.

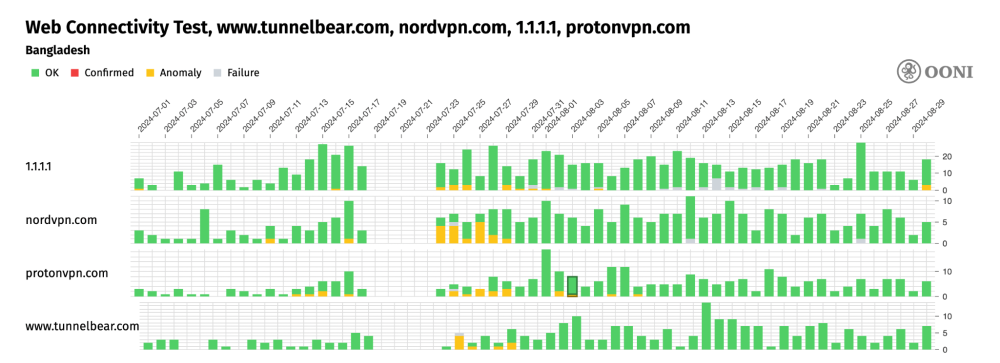

- Crackdown on circumvention: Authorities extended controls to VPNs, including ProtonVPN, NordVPN, and TunnelBear, hindering efforts to bypass censorship and share evidence of abuses, particularly during the July 31–August 5 phase.

List of acronyms

AL – Awami League

AS – Autonomous System

BCL – Bangladesh Chhatra League

BEC – Bangladesh Election Commission

BGB – Border Guard Bangladesh

BNP – Bangladesh Nationalist Party

BTRC – Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission

CAIDA – Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (developer of IODA)

CDN – Content Delivery Network

CU – Chittagong University

DB – Detective Branch (of Dhaka Metropolitan Police)

DU – Dhaka University

DoT – Department of Telecommunications

ICT – Information and Communications Technology

IIG – International Internet Gateway

IODA – Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (Georgia Tech/CAIDA)

IP – Internet Protocol

ISP – Internet Service Provider

ISPAB – Internet Service Providers Association of Bangladesh

ITC – International Terrestrial Cable

JU – Jahangirnagar University

MNO – **Mobile Network Operator

NTMC – National Telecommunication Monitoring Centre

OONI – Open Observatory of Network Interference

PS core – Packet Switched core

RU – Rajshahi University

SUST – Shahjalal University of Science and Technology

TLS – Transport Layer Security (protocol)

VPN – Virtual Private Network

Introduction

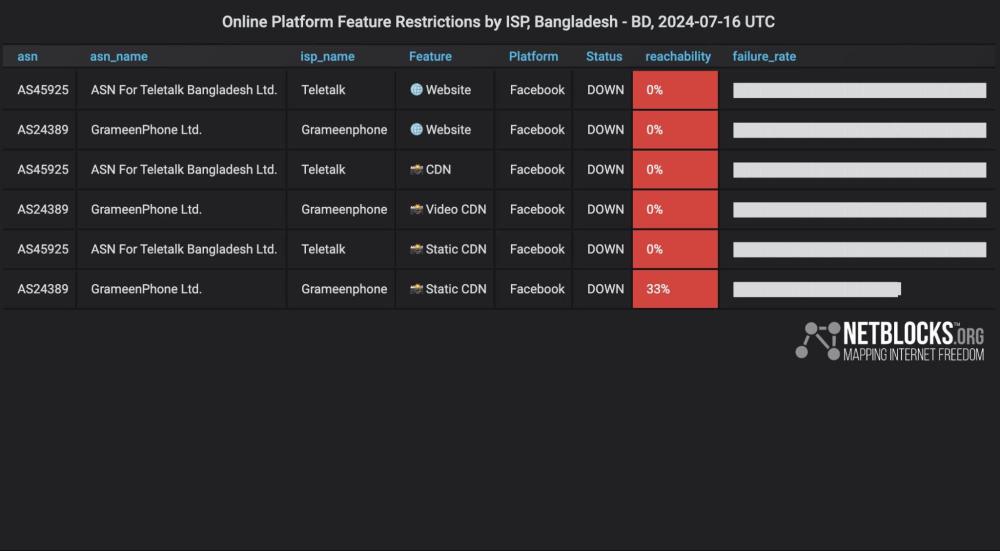

During the student-led uprising between July 15 and August 5, 2024, Bangladesh experienced a series of internet shutdowns that varied in form, intensity, and geographic reach. While internet disruptions have occurred in the country since 2009, the July–August 2024 shutdown was unprecedented – both in scope, due to its nationwide impact, and in duration, marking the longest sustained disruption to date. The array of tactics used by the authorities to restrict access, ranging from full blackouts to bandwidth throttling and selective blocking, made it broader and more complex than any previous incident.

Compounding the severity of these shutdowns was the opacity with which they were carried out. The lack of publicly disclosed directives and the shifting methods of enforcement created confusion and made it difficult to document events as they unfolded. This report draws on news coverage published during the uprising and in the aftermath of Sheikh Hasina’s fall from power, as well as technical data from international internet monitoring organizations and interviews with service providers and authorities.

Although the overall period spans 22 days, internet connectivity was disrupted for 20 of those days, with August 1 and 3 standing out as days when no significant disruption was reported. This report divides the 22-day period into five phases, documenting each phase’s political developments, patterns of protest and repression, and the specific forms of network control imposed. It examines not only when shutdowns occurred and what form they took, but also the mechanisms and institutions through which they were executed. Its goal is to reconstruct a verified timeline, linking disruption to its political backdrop, technical characteristics, and chain of responsibility.

What Is an Internet Shutdown?

The #KeepItOn coalition defines an internet shutdown as “an intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information.” Shutdowns are typically ordered by state authorities and implemented through technical means to limit access to information, suppress communication, or control public mobilization during periods of political unrest or perceived instability. Shutdowns may take several forms:

- Blackout: A complete disconnection of internet services, including mobile data and fixed-line broadband.

Throttling: A deliberate reduction of internet speed (such as downgrading from 4G to 2G) making regular use of the internet difficult or impossible. - Blocking: Targeted disruptions of access to specific platforms, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, or YouTube, usually through DNS tampering, IP blocking, or filtering at the gateway level.

At their core, shutdowns disconnect large segments of the population from communication, information, and essential services, and are often implemented without transparency or due process.

How are Shutdowns Implemented?

In Bangladesh, internet shutdowns are typically initiated through instructions from state authorities including the regulator, Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC). Authorities issue formal or informal orders to mobile network operators (MNOs) and internet service providers (ISPs) to block access, reduce speeds, or shut down connectivity entirely (often referred to as triggering a “kill switch”). Targeted disruptions of access to specific platforms, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, or YouTube, are usually implemented through DNS tampering, IP blocking, or filtering at the gateway level.

The centralized structure of Bangladesh’s internet infrastructure makes such enforcement relatively straightforward. All domestic internet traffic must pass through a limited number of International Internet Gateways (IIGs), which serve as chokepoints through which access to the global internet is routed. Such centralization allows the authorities to implement shutdowns either by instructing individual ISPs or by applying restrictions upstream at the IIG level – affecting all downstream users simultaneously.

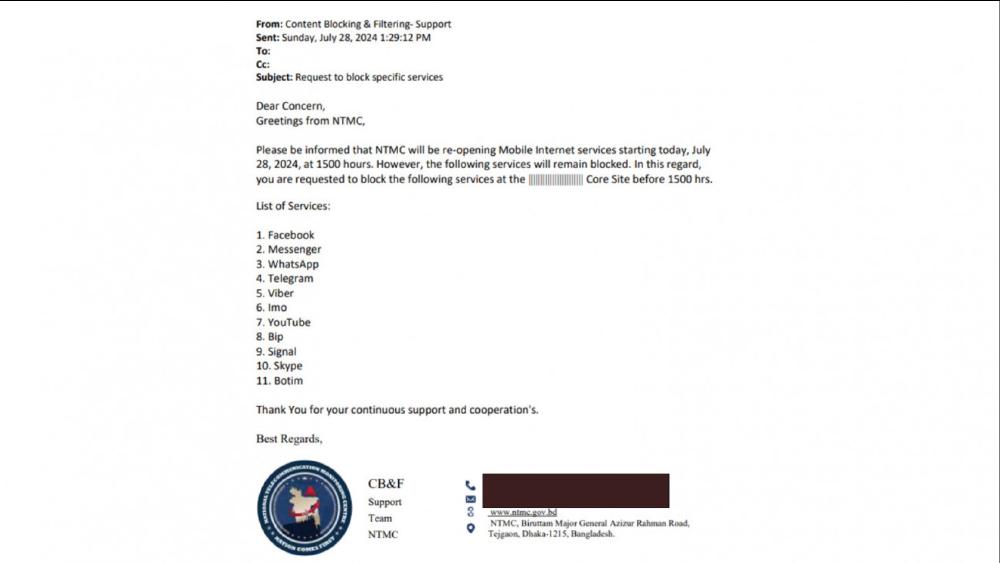

In some instances, according to the industry insiders, state agencies with technical capacity, such as the National Telecommunication Monitoring Centre (NTMC) – may directly intervene in network operations without the involvement of private providers. The Centre also provides directives to the operators and service providers to censor the internet. However, due to the lack of formal, publicly disclosed procedures, these directives often remain in the dark and implemented with almost no resistance from the service providers.

Internet shutdowns in Bangladesh can be localized, regional, or nationwide. Their scope may vary, and duration can range from minutes to weeks, depending on the intent and technical method used. From a brief blackout in November 2015, to nationwide mobile internet throttling during the 2018 student protests, to platform blocking in 2021, shutdowns have been imposed in different forms. However, the July–August 2024 shutdown blackouts, throttling, and platform blocking were deployed simultaneously at a national scale and sustained over multiple weeks.

Methodology

This timeline and analysis were reconstructed using a range of publicly available sources and digital evidence. Throughout the protest period, our team monitored media reports, social media posts, official statements, and platform behavior to document when, where, and how internet disruptions occurred.

We also relied on network measurement data from platforms such as IODA and OONI to verify the timing and scale of shutdowns. These technical signals were crucial in corroborating media reports, especially during moments of complete information blackout. Interviews with key stakeholders, including those from the government, IIGs, ITCs, and MNOs, offered additional context on the implementation mechanisms.

Where possible, firsthand experiences were documented by the research team and cross-referenced with public reports. The fragmented and often conflicting nature of available information meant that the timeline was assembled iteratively, with constant back-checking and source triangulation.

Limitations

Due to the opacity of government communication, we were unable to access formal written orders for most instances of internet shutdowns, platform blocks, and VPN disruptions. Much of the timeline had to be reconstructed using news reports, corroborated operator interviews, infrastructure behavior (such as cache server shutdowns), and data from network monitoring platforms.

For this report, we primarily relied on death counts reported in national newspapers during the July-August 2024 uprising. These contemporaneous reports were used to infer patterns of violence and their correlation with periods of intensified internet shutdowns. Later, government and UN reports provided differing figures. For instance, the Ministry of Health’s count, which was later cited by the UN Human Rights Office report released in February 2025, recorded 841 deaths. It was estimated that as many as 1,400 people had died between July 15 and August 5, 2024, including women and children, with the vast majority killed by firearms.

However, neither government bodies nor the UN have released disaggregated or day-specific fatality figures that allow for precise time-coded analysis. As such, while this report identifies broad overlaps between the most intense periods of network disruption and spikes in media-reported violence, it was not possible to draw precise statistical conclusions without verified, time-coded casualty datasets.

OONI methodology

Since 2012, OONI has developed free and open source software (called OONI Probe) which is designed to measure various forms of internet censorship, including the blocking of websites and apps. Every month, OONI Probe is regularly run by volunteers in around 170 countries, including Bangladesh. By default, network measurements collected by OONI Probe users are automatically published as open data in real-time.

OONI Probe includes the Web Connectivity experiment which is designed to measure the blocking of many different websites (included in the public, community-curated Citizen Lab test lists). Specifically, OONI’s Web Connectivity test is designed to measure the accessibility of URLs by performing the following steps:

- Resolver identification

- DNS lookup

- TCP connect to the resolved IP addresses

- TLS handshake to the resolved IP addresses

- HTTP(s) GET request following redirects

The above steps are automatically performed from both the local network of the user, and from a control vantage point. If the results from both networks are the same, the tested URL is annotated as accessible. If the results differ, the tested URL is annotated as anomalous, and the type of anomaly is further characterized depending on the reason that caused the failure (for example, if the TCP connection fails, the measurement is annotated as a TCP/IP anomaly).

Anomalous measurements may be indicative of blocking, but false positives can occur. We therefore consider that the likelihood of blocking is greater if the overall volume of anomalous measurements is high in comparison to the overall measurement count (compared on an ASN level within the same date range for each OONI Probe experiment type).

Each Web Connectivity measurement provides further network information (such as information pertaining to TLS handshakes) that helps with evaluating whether an anomalous measurement presents signs of blocking. We therefore disaggregate based on the reasons that caused the anomaly (e.g. connection reset during the TLS handshake) and if they are consistent, they provide a stronger signal of potential blocking.

Based on OONI’s heuristics, we are able to automatically confirm the blocking of websites based on fingerprints if a block page is served, or if DNS resolution returns an IP known to be associated with censorship. While this method enables us to automatically confirm website blocking in Bangladesh and numerous other countries (such as Italy, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Indonesia), not all blocks are implemented in a way that is fingerprintable and automatically detectable.

We therefore aggregate anomalous web connectivity measurements based on failure types (“dns”, “tcp_ip”, “http-failure”, “http-diff”) to evaluate if they were consistently present (or if the types of failures varied), as a more consistent failure type observed in a larger volume of measurements provides a stronger signal of blocking. We further analyze these failures to detect the specific errors (such as “connection_reset_error” or “generic_timeout_error”) that would enable us to characterize potential blocking, and we aggregate the errors to examine whether and to what extent they were consistent across (relevant) measurements on each tested ASN.

This involved analyzing the network information from TLS handshake data in these measurements to evaluate whether the errors were a result of TLS based interference. For example, a measurement may show that DNS resolution returned consistent IPs, that it was possible to establish a connection to resolved IPs, but that the TLS handshake session timed out after the first ClientHello message (which is unencrypted), resulting in a “generic_timeout_error”. While we would consider that such a measurement shows signs of potential TLS based interference, we would not draw conclusions from a single measurement alone.

We therefore aggregate the errors to determine whether a large percentage of anomalous measurements for a tested URL presented the same error (e.g. “tls_timeout_error”) in comparison to the overall measurement volume on a specific network, within a specified date range. The higher the ratio of consistent errors (from anomalous measurements) in comparison to the overall measurement count, the stronger the signal (and the greater our confidence) that access to the tested domain is (a) blocked, and (b) blocked in a specific way (e.g TLS interference).

The OONI findings of this report present several limitations:

- Date range of analysis. The findings are limited to OONI network measurement data collected from Bangladesh between 1st July 2024 to 31st August 2024, when the internet disruptions and blocks reportedly occurred amid the student-led uprising of the summer of 2024.

- Measurement coverage. The availability of OONI data depends on whether, on which networks, and when an OONI Probe user ran tests in Bangladesh. As OONI Probe is used on a voluntary basis, OONI has no control over the availability of measurements. As a result, OONI measurement coverage in Bangladesh varies over time.

- Tested ASes. While OONI Probe tests are regularly performed on multiple ASes in Bangladesh, not all networks are tested equally. Rather, the availability of measurements depends on which networks OONI Probe users were connected to when performing tests. As a result, OONI measurement coverage varies across ASes over time in Bangladesh. Moreover, the findings are limited to the ASes which received the largest measurement coverage and which presented the strongest blocking signals during the analysis period.

- Blocking signals. As part of their data analysis, OONI limited their findings to signals that they considered more reliable and indicative of government-commissioned censorship, while excluding cases viewed as presenting weak signals (due to limited measurement coverage and inconsistent failure types).

A Timeline of the July Shutdown

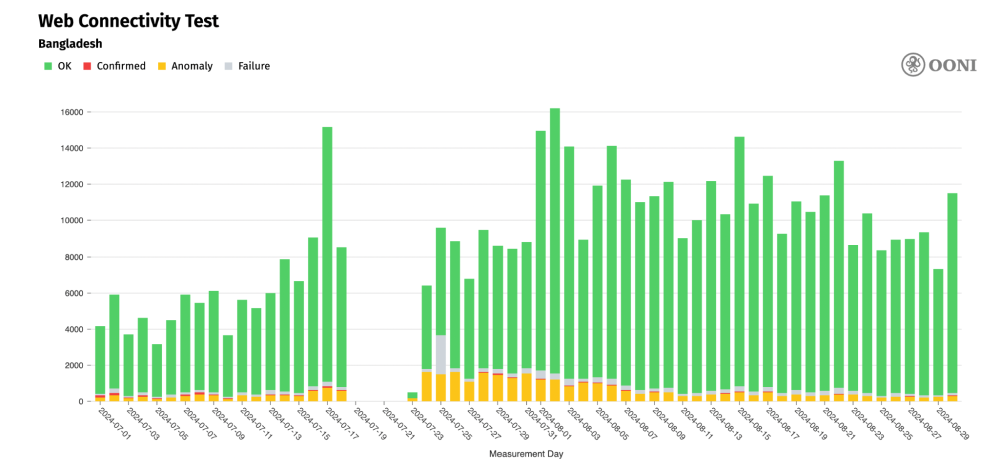

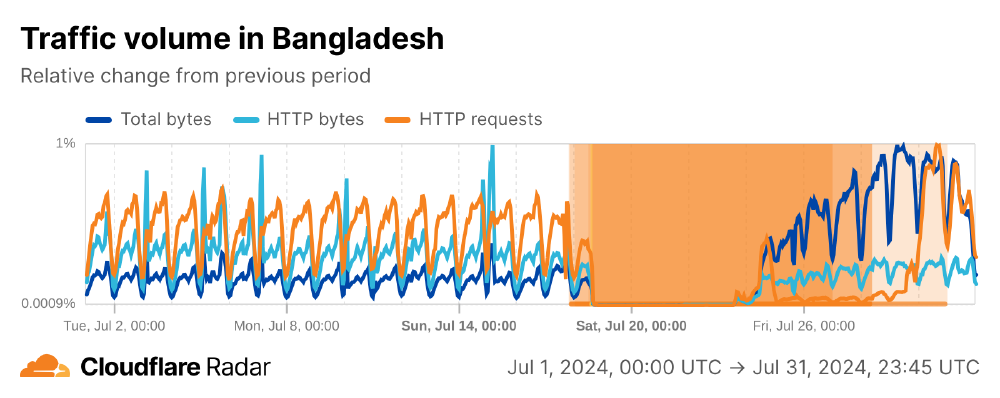

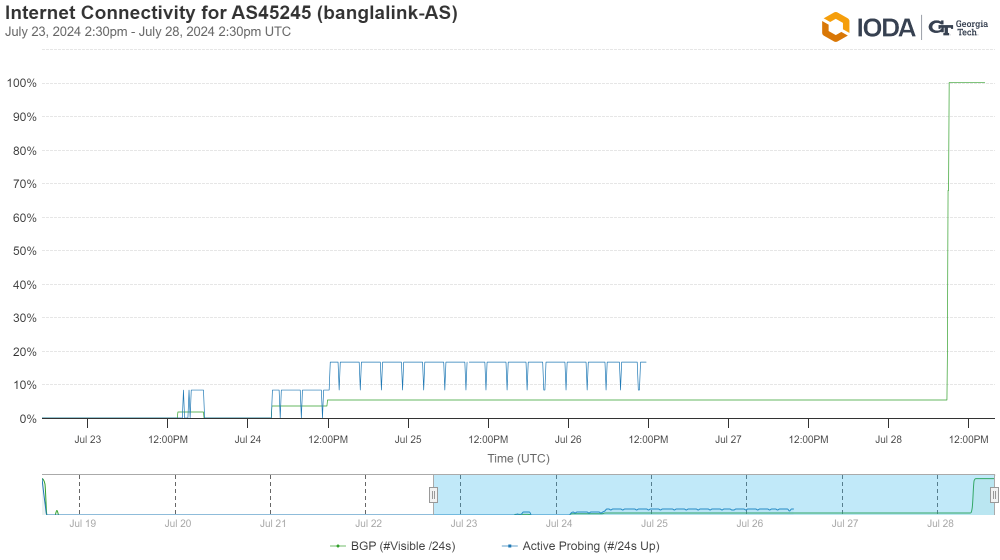

The July-August 2024 internet shutdown in Bangladesh is likely one of the most extensively documented in the country’s history. From the very first day, each instance of disruption was reported in some form by local and national news outlets. Following the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s government, further reporting examined the scope, methods, and political context of the shutdown. Internet users were also vocal throughout the period, sharing real-time reports of service disruptions on social media. Several local and international watchdog organizations collected technical measurement data during this time, producing reliable evidence of the censorship.

This report draws on media coverage, technical evidence, and interviews with operators, service providers, and regulators to reconstruct a verified timeline of the shutdown and understand how each phase of disruption was carried out.

a) July 15–17: Escalating Protests and Initial Internet Controls

Political Context

The anti-discrimination protests escalated on July 14, shortly after a controversial remark by then–Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who stated, “If the grandchildren of the freedom fighters don’t get quota benefits, should the grandchildren of Razakars get the benefit?” The term “Razakar” refers to collaborators of the Pakistani Army during the 1971 Liberation War, which is deeply tied to national trauma and betrayal. The statement was seen as offensive and as an attempt to imply that the protesting students were descendants of Razakar. That evening, demonstrations broke out across public university campuses. By July 15, tensions deepened as activists from the ruling Awami League’s student wing, Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), launched attacks on protesters at several campuses, turning universities into flashpoints of violence.

On July 16, students from private universities and other institutions joined the movement. The first reported death occurred that day: in Rangpur, a video showing police firing on Abu Sayed, a student at Begum Rokeya University, circulated widely. Media reports published the same day indicated at least six deaths. On that very day, general students fought back and drove the BCL activists out of Dhaka and Rajshahi Universities in the university campuses.

Later that night, all public and private universities across the country were declared closed indefinitely. Students were ordered to vacate their dormitories. On July 17, many were forcibly evicted and took shelter in surrounding areas. Students tried to hold “absentee funerals” for those who were killed, but police attacked their gatherings at three universities. As a result, protests spread from public campuses to private universities and beyond.

Nature of the Shutdown

Between July 15 and 17, three key forms of internet control were reported: mobile internet throttling, targeted mobile service shutdowns, and selective platform blocking.

Complaints of slow mobile data (indicating throttling) in the Dhaka University area began on the night of July 14. By the morning of July 15, both 3G and 4G services were reportedly disabled in the Shahbagh and DU areas. As clashes spread, high-speed mobile internet was similarly shut down in other major university zones from midnight (July 15-16) onward.

From July 16, users outside these university areas also began reporting degraded connectivity. This included either a complete inability to access 3G/4G services or significant disruptions when attempting to open Facebook or Messenger on mobile networks. Importantly, at this time, Facebook remained accessible via broadband connections.

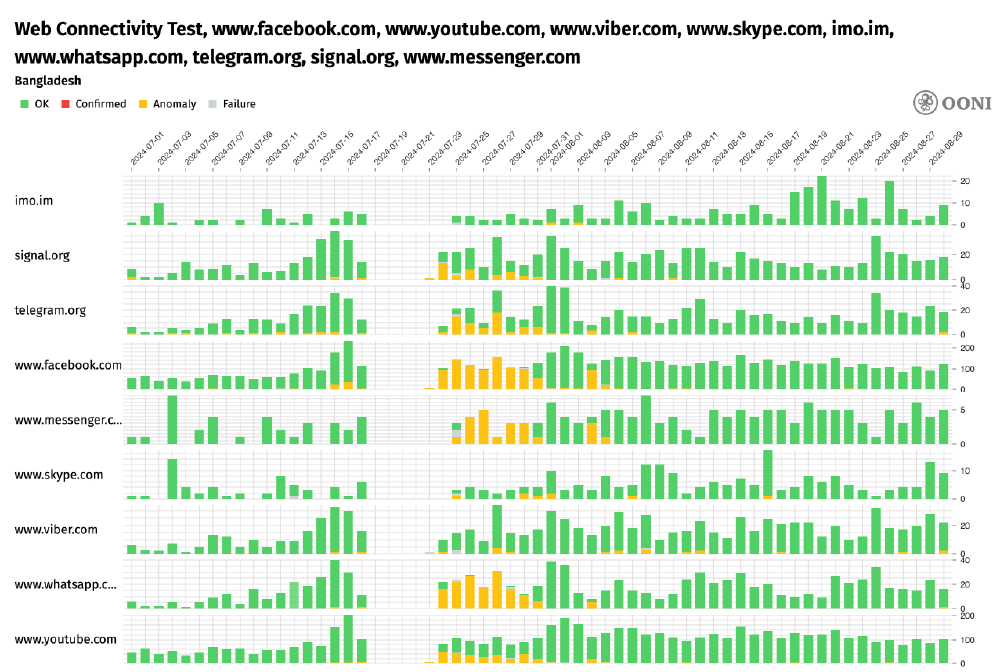

Independent OONI Probe network tests conducted by Digitally Right’s network measurement fellows on July 16 and 17 in six districts – including Dhaka, Sylhet, Tangail, Mymensingh, and Rangpur – suggested that Facebook was blocked across all major mobile networks by the night of July 16.

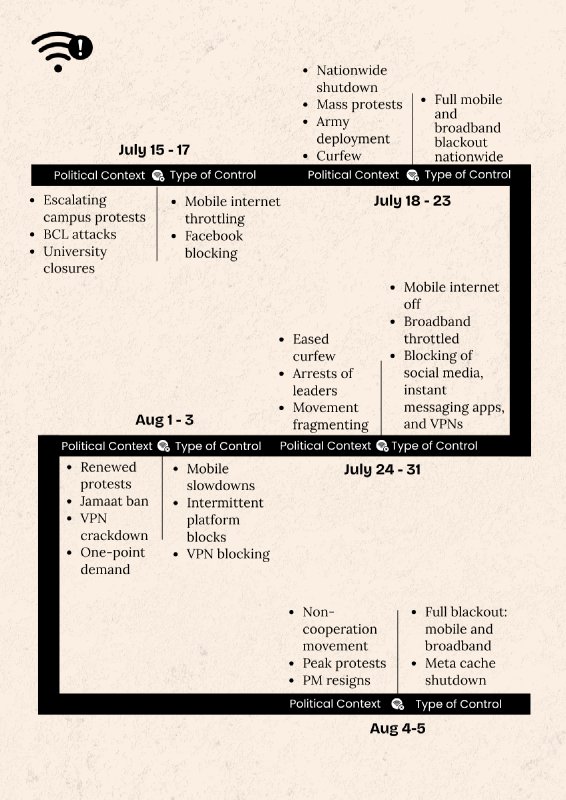

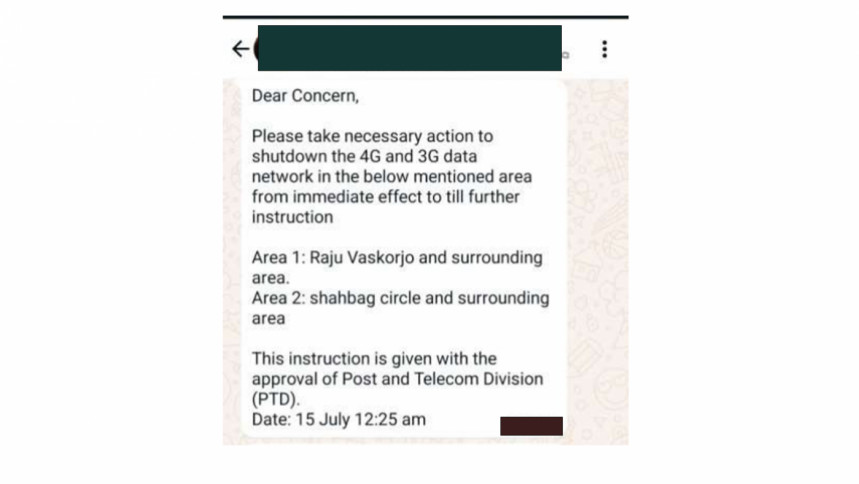

Image 1: Screenshots of OONI Probe test results showing the blocking of Facebook on networks in Bangladesh on 16th July 2024 (source: OONI Probe app).

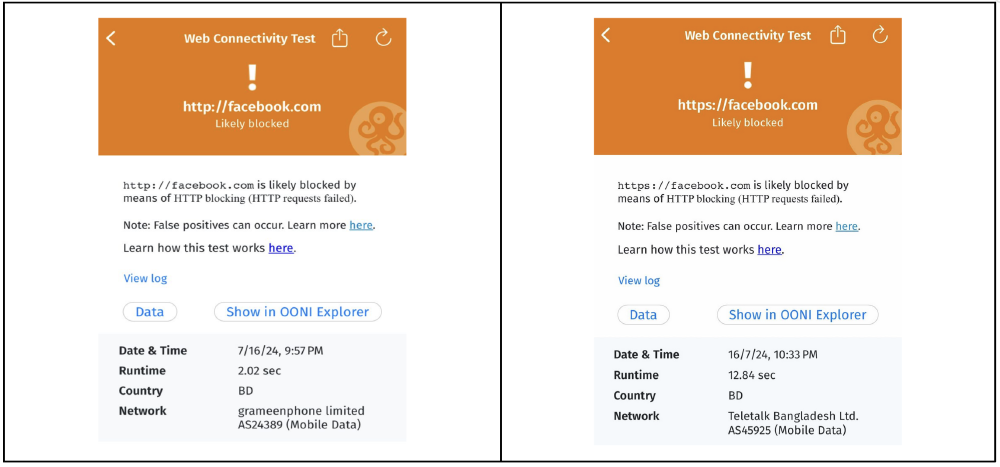

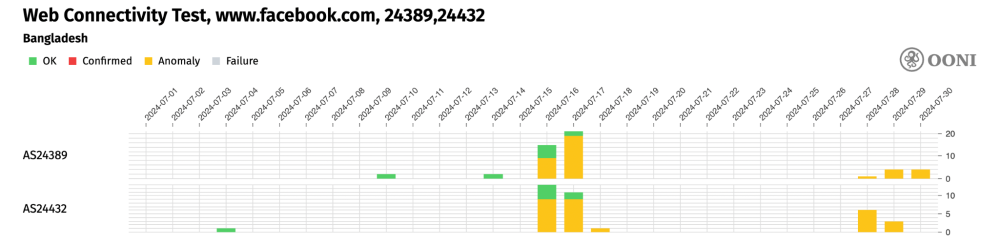

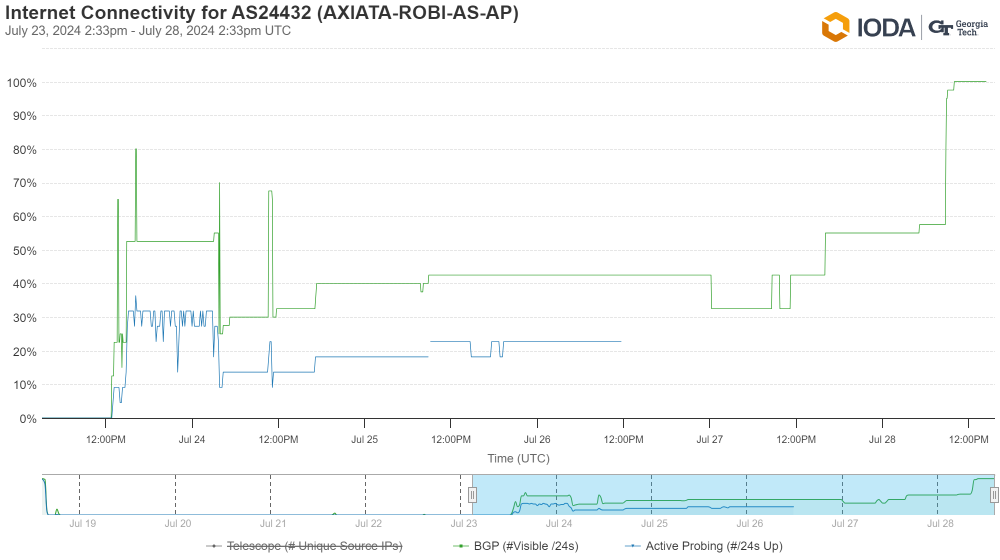

While OONI data collected from multiple networks in Bangladesh throughout July 2024 indicates that Facebook was accessible on most networks, access to “www.facebook.com” appears to have been blocked on the AS24432 (Axiata) and AS24389 (Grameenphone) networks, starting from 16th July 2024.

Chart 1 aggregates OONI measurement coverage from the testing of “www.facebook.com” on the AS24432 (Axiata) and AS24389 (Grameenphone) networks in Bangladesh throughout July 2024.

Chart 1: OONI Probe testing of www.facebook.com in Bangladesh on the AS24432 (Axiata) and AS24389 (Grameenphone) networks between 1st July 2024 to 31st July 2024 (source: OONI data).

As is evident from chart 1, most OONI measurements from the testing of “www.facebook.com” on the AS24432 and AS24389 networks resulted in anomalies (signals of potential censorship) on 16th and 17th July 2024 – the timing of which correlates with the protests in Dhaka. However, the availability of measurements from these networks from previous days is very limited, presenting an important limitation to this finding.

It’s worth noting though that most measurements from both networks on 16th and 17th July 2024 resulted in failures (timeout errors and connection reset errors) during the TLS handshake, suggesting the presence of TLS level interference. This is further suggested by the OONI data, which shows that connections to the resolved IPs were successful, reducing the likelihood of the anomalies being false positives triggered by transient network failures. Moreover, Facebook interference on the AS24432 and AS24389 networks is further suggested by the OONI data showing that most other tested websites were accessible on these networks on 16th July 2024, while the testing of several Facebook endpoints presented anomalies (further suggesting Facebook blocking).

Quite similarly, OONI data suggests the potential temporary blocking of WhatsApp on 17th July 2024 between 7:00 to 9:00 am UTC. More specifically, OONI data from the testing of WhatsApp in Bangladesh on 17th July 2024 shows that while most connections to WhatsApp endpoints succeeded, attempted connections to WhatsApp’s registration service and WhatsApp Web failed, resulting in connection reset errors. However, the limited volume of measurement coverage during this period limits our ability to confirm WhatsApp blocking with confidence.

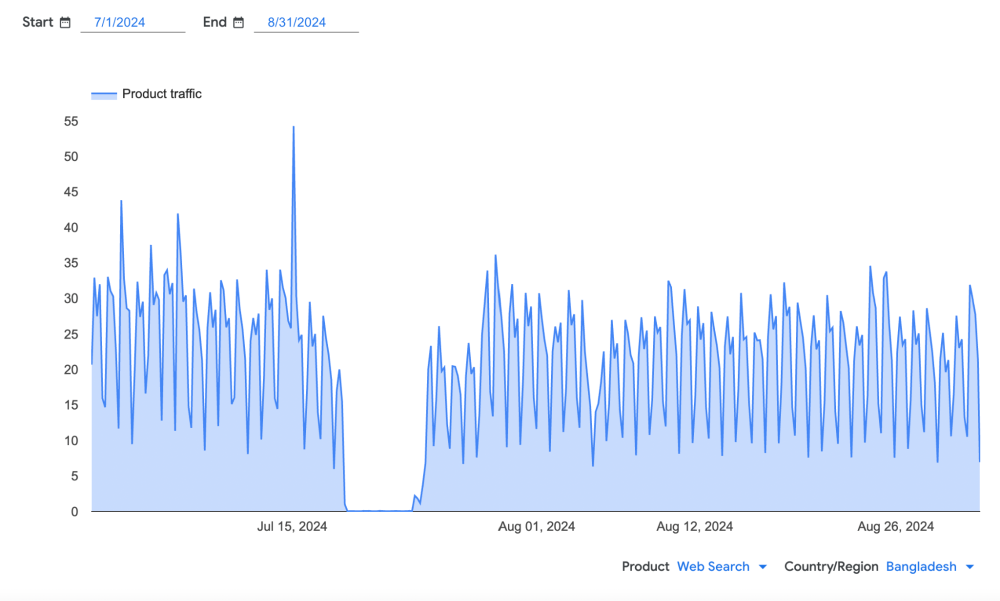

Various media outlets reported the issue prominently, and the network monitoring group NetBlocks reported that access to Facebook had been restricted on several networks.

Image 2: Netblocks report on Facebook restrictions on networks in Bangladesh on 16th July 2024 (source: X).

How It Happened

The implementation of shutdown measures during this period was marked by opacity, limited disclosure, and overlapping authority. No official announcements were made to inform users about the disruptions. Available information was pieced together through retrospective media investigations, technical data, and interviews with network providers.

| Phase | Political context | Type of control | Network layer involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 15-17 | Escalating campus protests, BCL attacks, and university closures | Mobile internet throttling, Facebook blocking | Mobile operator-level throttling, TLS interference, BTRC and NTMC directive |

| July 18-23 | Nationwide shutdown, mass protests, army deployment, curfew | Full mobile and broadband blackout nationwide | IIG, ITC, Submarine Cable, BTRC directives |

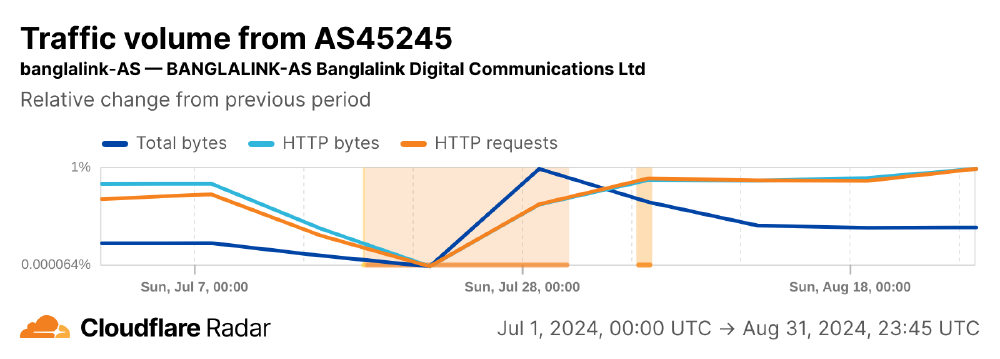

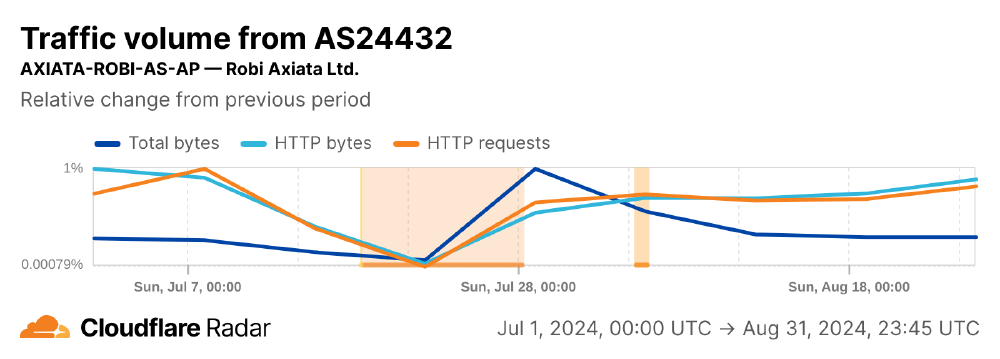

| July 24-31 | Eased curfew, arrests of leaders, movement fragmenting | Mobile internet off, broadband throttled, blocking of social media, instant messaging apps, and VPNs | IIG cache blocks, ISP throttling, TLS interference, IP-level blocks, NTMC directive on platform blocks |

| Aug 1-3 | Protests shift to one-point demand, ban on Jamaat-e-Islami | Mobile slowdowns, intermittent platform blocks | NTMC order, platform blocks on mobile internet |

| Aug 4-5 | Non-cooperation movement, peak protests, PM resigns | Full blackout: mobile and broadband, Meta cache shutdown | Mobile + IIG + ISP + cache all disabled on government order |

Key takeaways

- Unprecedented scale and duration: The July–August 2024 internet shutdown was the longest and most geographically extensive in Bangladesh’s history, marking a significant escalation of digital control.

- Evolution of censorship tactics aligned with protest milestones: Authorities deployed a broad and evolving arsenal of control methods, from complete nationwide mobile blackouts and broadband throttling to sophisticated selective platform blocking.

- Correlation between intense shutdowns and casualties: The most intense periods of network disruption, particularly full blackouts, broadly coincided with spikes in reported violence and casualties during the anti-discrimination movement.

- Deliberate opacity and fragmented authority: Shutdowns were carried out with a stark lack of official disclosure, relying on informal directives (e.g., via WhatsApp) and involving multiple government entities (BTRC, NTMC, DoT) often operating with overlapping or unclear lines of authority, leading to confusion.

- Targeted crackdown on circumvention tools: Authorities actively worked to thwart circumvention efforts, including a crackdown on VPNs (like Proton VPN) and other free apps, making it significantly harder for users to bypass restrictions.

- Leveraging service providers for implementation: Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and International Internet Gateways (IIGs), along with mobile operators, were extensively utilized to implement censorship, often being instructed to disable cache servers and comply with verbal or informal directives.

- Internet control as a central state response to protest: The entire episode highlights how internet shutdowns and censorship were not isolated incidents but a dynamic and central tool used by the state to control information flow, suppress dissent, and manage the public narrative during a period of profound political and social upheaval.

Conclusion

The internet shutdown enforced across Bangladesh between July 15 and August 5, 2024, represents an unprecedented and highly complex chapter in the nation’s history of digital control. This period of censorship, unmatched in both its nationwide scope and sustained duration, coincided directly with the peak of the anti-discrimination movement and a tumultuous political transition.

This timeline shows that the shutdown was neither uniform nor transparent. Instead, it was characterized by inconsistent enforcement, conflicting official statements, and the absence of clear legal orders, making it difficult for citizens, journalists, and digital rights actors to respond or verify information in real time.

At a moment of mass mobilization and regime change, control over digital connectivity often becomes central to the state’s response. Understanding how these shutdowns are implemented and their cumulative effect on political expression, access to information, and human rights is critical not only for accountability but also for prevention. We hope that this timeline and analysis will serve as a vital resource for researchers, human rights organizations, and digital watchdogs in their ongoing efforts to understand, document, and ultimately prevent similar abuses of internet freedom.

References

- Abdullah, M. (2024, August 13). Probe reveals deliberate internet blackout to suppress quota reform movement. Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/354596/btrc-ntmc-behind-internet-shutdown-palak-issued

- Abdullah, S. (2024, November 5). Shutdown watch: Building a community against internet shutdowns in bangladesh. Internet Society Pulse. https://pulse.internetsociety.org/blog/shutdown-watch-building-a-community-against-internet-shutdowns-in-bangladesh

- Afrin, S. (2024, August 13). BTRC and NTMC shut down internet, Palak phoned too. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/7rh73pjode

- Ahmed, R. (2024, July 28). Government itself shut down internet. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/iv2dsrbrfk

- Ali, A. C., Marium. (n.d.). How bangladesh’s ‘gen z’ protests brought down pm sheikh hasina. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2024/8/7/how-bangladeshs-gen-z-protests-brought-down-pm-sheikh-hasina

- All public, private universities closed indefinitely; students asked to vacate halls. (2024, July 16). The Business Standard. https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/education/all-public-private-universities-closed-indefinitely-901056

- bdnews24.com. (2015, November 18). Internet access restored in Bangladesh after brief shutdown. Internet Access Restored in Bangladesh After Brief Shutdown. https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/internet-access-restored-in-bangladesh-after-brief-shutdown

- Bergin, J., Lim, L., Nyein, N., & Nachemson, A. (2022, August 29). Flicking the kill switch: Governments embrace internet shutdowns as a form of control. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/29/flicking-the-kill-switch-governments-embrace-internet-shutdowns-as-a-form-of-control

- Broadband, 4G internet services restored. (2024, August 5). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/353724/broadband-internet-service-restored-after-3-hours

- Broadband internet restored in limited areas after blackout. (2024, July 24). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/352554/broadband-internet-restored-in-limited-areas-after

- Broadband, mobile internet restored. (2024, August 5). The Business Standard. https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/broadband-internet-disrupted-places-dhaka-910011

- BSS. (2024, July 29). Quota movement coordinators not forced to issue statement: DB chief. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/xtaxw5o5vt

- BTRC instructs IIGs to increase internet speed across country. (n.d.). The Financial Express. https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/btrc-instructs-iigs-to-boost-internet-speed-across-country

- CBC. (2024, July 19). Nationwide curfew in Bangladesh as deadly protests over government jobs escalate. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/bangladesh-jobs-protests-telecoms-cut-1.7268940

- Chowdhury, M., & Henderson, L. (n.d.). Internet Shutdown Advocacy in Bangladesh: How to Prepare, Prevent Resist. https://preparepreventresist.openinternetproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Optima-Bangladesh-Report.pdf

- Correspondent. (2024a, July 29). Students demonstrate in front of RU. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/local-news/zxqt3ngkow

- Correspondent. (2024b, August 2). Didn’t announce withdrawal of movement voluntarily: Six coordinators in joint statement. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/cigx71vi3p

- Correspondent, D. U. (2024c, July 15). PM’s Quota Remark: Late-night protests rock DU, other universities. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/pms-quota-remark-late-night-protests-rock-du-other-universities-3657201

- Correspondent, S. (2024a, July 19). Internet service blocked across the country. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/internet-service-blocked-across-the-country-3660596

- Correspondent, S. (2024c, July 25). Broadband restored on trial. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/broadband-restored-trial-3661356

- Correspondent, S. (2024d, July 29). 15 injured in attack on protesters at Barishal Uni, demonstrations at BM College. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/local-news/dkmf611ost

- Correspondent, S. (2024e, July 29). Cops charge baton at protestors at ECB Chattar, 20 detained from Mirpur, Dhanmandi. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/city/rr1h6i77fq

- Correspondent, S. (2024f, July 29). DB custody: 6 coordinators announce withdrawal of programme. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/1a5pu53bbq

- Correspondent, S. (2024g, July 30). Jamaat to be banned through executive order by Wednesday: Law minister. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/politics/nzlm53rf3g

- Correspondent, S. (2024h, July 31). March for Justice: Students face police resistance, arrests across country. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/7rtmv6141n

- Correspondent, S. (2024i, July 31). Protesting students announce fresh programme “remembering our heroes” Thursday. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/dmkanm6oj3

- Correspondent, S. (2024j, August 2). Facebook, Messenger resume on mobile internet after 5-hr disruption. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/science-technology/ivjcn3yi1o

- Correspondent, S. (2024k, August 2). Protests, demonstrations all over city, demands for justice. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/5dx6tsauyh

- Correspondent, S. (2024l, August 2). Students against discrimination to hold ‘prayers and mass procession’ today. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/i7vwh1x14x

- Correspondent, S. (2024m, August 3). Students against discrimination announces new programmes for saturday, sunday. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/nsjuagpio9

- Correspondent, S. (2024n, August 3). Students Against Discrimination declares one-point demand for govt’s resignation. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/rd12isd6ni

- Correspondent, S. (2024o, August 4). Facebook, Messenger, WhatsApp, Instagram, mobile internet ordered to be shut down. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/r6w5a3mpcy

- Correspondent, S. (2024p, August 4). Students against discrimination’s ‘march to dhaka’ on monday. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/xlv47rs3c3

- Correspondent, S. (2024q, August 4). Three days of public holiday from Monday. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/k26kmf1n06

- Correspondent, S. (2024r, August 5). Broadband internet restored. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/gm0o97gu3x

- Correspondent, S. (2024s, August 5). Cooperate with us, all the killings will be brought to trial: Army chief. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/gg699hf4gf

- Correspondent, S. (2024t, August 5). Crowd breaks into Ganabhaban. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/city/fl10zveq9o

- Desk, P. A. (2024, August 12). 109 killed in clashes in a single day. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/qhf6h8cwxy

- Desk, P. A. E. (2024, August 3). 2 killed in mass processions, clashes across country. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/nd2t409kax

- Facebook, other social media platforms back online. (2024, August 5). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/353739/facebook-other-social-media-platforms-back-online

- OONI Facebook Messenger test. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/nettest/facebook-messenger/

- OONI Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). (n.d.-a). https://ooni.org/support/faq/

- OONI Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). (n.d.-b). https://ooni.org/support/faq/

- OONI Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). (n.d.-c). https://ooni.org/support/faq/

- OONI Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). (n.d.-d). https://ooni.org/support/faq/

- Google transparency report. (n.d.). https://transparencyreport.google.com/traffic/overview?hl=en&fraction_traffic=start:1719792000000;end:1725148799999;product:19;region:BD&lu=fraction_traffic

- Hasan, M. (2024a, August 1). IT firms suffer low productivity amid slow internet. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/it-firms-suffer-low-productivity-amid-slow-internet-3666826

- Hasan, M. (2024b, August 13). What you need to know about internet crackdown in Bangladesh. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/what-you-need-know-about-internet-crackdown-bangladesh-3676346

- Internet censorship in bangladesh—OONI explorer. (n.d.). https://explorer.ooni.org/country/BD

- Documentation on Interpreting OONI data. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/support/interpreting-ooni-data/

- IODA. (n.d.-a). https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/country/BD?from=1719866792&until=1725137192

- IODA. (n.d.-c). https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/resources?tab=glossary

- IODA. (n.d.-e). https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/asn/45245?from=1721757679&until=1722189679

- IODA. (n.d.-f). https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/asn/24432?from=1721757679&until=1722189679

- IODA. (n.d.-g). https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/country/BD?from=1722804392&until=1722977192

- Islam, R. (2024a, July 29). 4G internet service becomes slower from Monday afternoon. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/0wn7j3e5hs

- #KeepItOn: Fighting internet shutdowns around the world. (n.d.). Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/campaign/keepiton/

- Mobile access to Facebook restored after nearly 6hrs. (2024, August 2). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/353476/mobile-access-to-facebook-restored-after-nearly

- Mobile internet shut down across Bangladesh again. (2025, July 28). https://www.newagebd.net/post/country/241641/mobile-internet-shut-down-across-bangladesh-again

- Moral, S. (2024, September 7). Student-people uprising: More than 18,000 injured. Prothomalo. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/1qyly6muhk

- NetBlocks. (2024, July 17). Confirmed: Live metrics show that social media platform Facebook has been restricted on multiple internet providers in #Bangladesh. X.com. https://x.com/netblocks/status/1813293423157555534

- OONI Test Descriptions. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/nettest/

- OHCHR. (n.d.). Human Rights Violations and Abuses related to the Protests of July and August 2024 in Bangladesh. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/bangladesh/ohchr-fftb-hr-violations-bd.pdf

- OONI Explorer—Bangladesh blocked news media websites amid 2024 general elections. (n.d.). https://explorer.ooni.org/findings/11686385001

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-a). https://explorer.ooni.org/search

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-i). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240716200350.966415_BD_webconnectivity_921a95b91bc1bdd3

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-j). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240716172647.769708_BD_webconnectivity_9e7c087cc444d1ee

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-k). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240717082919.245093_BD_webconnectivity_740ef4a92c6e58a5

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-l). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240716174236.351512_BD_webconnectivity_319be948792b4860

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-m). https://explorer.ooni.org/chart/mat

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-n). https://explorer.ooni.org/chart/mat

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-o). https://explorer.ooni.org/chart/mat

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-p). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240717074637.449725_BD_whatsapp_e9b5a10845b26966

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-q). https://explorer.ooni.org/countries

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-r). https://explorer.ooni.org/chart/mat

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-s). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240728154829.417947_BD_webconnectivity_1d7f5d5f8c3ea3e1

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-t). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240730231624.142954_BD_webconnectivity_3f2f6ec0a71e29a8

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-u). https://explorer.ooni.org/m/20240727022246.281399_BD_webconnectivity_1637d085d44708de

- OONI Explorer—Open data on internet censorship worldwide. (n.d.-v). https://explorer.ooni.org/chart/mat

- OONI Glossary. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/support/glossary/

- OONI, IODA, M-Lab, Cloudflare, Kentik, Planet, C., ISOC, & Article19 2022-11-29. (2022, November 29). Technical multi-stakeholder report on Internet shutdowns: The case of Iran amid autumn 2022 protests. https://ooni.org/post/2022-iran-technical-multistakeholder-report/

- OONI/blocking-fingerprints. (2025). [Python]. Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). https://github.com/ooni/blocking-fingerprints (Original work published 2022)

- Palak: Broadband internet services could be fully restored by Wednesday night. (2024, July 24). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/352620/palak-broadband-internet-services-could-be-fully

- Paul, R. (2024, July 16). Five killed in violent anti-quota protests in Bangladesh. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/bangladesh-deploys-police-job-protests-flare-up-2024-07-16/

- Report, S. B. (2024, August 2). Mobile access to Facebook restored after nearly six hours. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/mobile-access-facebook-restored-after-nearly-six-hours-3668056

- OONI Research reports: Blocking of circumvention tools. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/reports/circumvention/

- Roskomsvoboda, O. 2023-02-24. (2023, February 24). How Internet censorship changed in Russia during the 1st year of military conflict in Ukraine. https://ooni.org/post/2023-russia-a-year-after-the-conflict/

- Shutdown—Bangladesh. (2024, August 4). Internet Society Pulse. https://pulse.internetsociety.org/en/shutdowns/bangladesh-government-shuts-down-mobile-internet-again-amidst-protests/

- OONI Signal test. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/nettest/signal/

- Spec/nettests/ts-017-web-connectivity. Md at master · ooni/spec. (n.d.). GitHub. https://github.com/ooni/spec/blob/master/nettests/ts-017-web-connectivity.md

- Sun, D. (2024a, July 12). Mobile internet ‘controlled’ in protesting areas. Daily-Sun. https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/758138

- Sun, D. (2024b, August 5). Mobile internet suspended, social media blocked on broadband. Daily-Sun. https://www.daily-sun.com/post/760516

- OONI Telegram test. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/nettest/telegram/

- Test-lists/lists at master · citizenlab/test-lists. (n.d.). GitHub. https://github.com/citizenlab/test-lists/tree/master/lists

- Timeline of events leading to the resignation of bangladesh prime minister sheikh hasina. (2024a, August 5). Voice of America. https://www.voanews.com/a/timeline-of-events-leading-to-the-resignation-of-bangladesh-prime-minister-sheikh-hasina/7731456.html

- Traffic from AS24432. (n.d.). Cloudflare. https://radar.cloudflare.com/traffic/as24432?dateStart=2024-07-01&dateEnd=2024-08-31

- Traffic from AS45245. (n.d.). Cloudflare. https://radar.cloudflare.com/traffic/as45245?dateStart=2024-07-01&dateEnd=2024-08-31

- Traffic in Bangladesh. (n.d.). Cloudflare. https://radar.cloudflare.com/traffic/bd?dateStart=2024-07-01&dateEnd=2024-07-31

- UN report: 1,400 people killed in July uprising. (2025, February 12). Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/373524/un-report-1-400-people-killed-in-july-uprising

- Violent clashes erupt between police and protesters in Dhaka even after 6 die during campus protests. (2024, July 17). AP News. https://apnews.com/article/bangladesh-universities-close-hasina-quota-student-protest-77f82215bf8fce35f288ea39d812bcdb

- WhatsApp test. (n.d.). OONI. https://ooni.org/nettest/whatsapp/

- Web connectivity. (a, January 1). https://ooni.org/nettest/web-connectivity/

- WhatsApp test. (n.d.). https://ooni.org/nettest/whatsapp/

- Why is broadband internet so slow now?: Experts tell TBS. (2024, July 25). The Business Standard. https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/why-broadband-internet-so-slow-now-experts-tell-tbs-903381

- Xynou, M., Basso, S., Padmanabhan, R., Filastò, A., DefendDefenders, & Initiative 2021-01-22, D. P. (2021, January 22). Uganda: Data on internet blocks and nationwide internet outage amid 2021 general election. https://ooni.org/post/2021-uganda-general-election-blocks-and-outage/

- Xynou, M., Padmanabhan, R., Kyaw, P., Organization, M. I. for D., & Filastò2021-03-09, A. (2021, March 9). Myanmar: Data on internet blocks and internet outages following military coup. https://ooni.org/post/2021-myanmar-internet-blocks-and-outages/

- Yu, A. (2024, August 5). Situation in Bangladesh. Telenor Asia. https://www.telenorasia.com/announcements/situation-in-bangladesh/

- কোটা আন্দোলন: দশদিন পর মোবাইল ইন্টারনেট চালু, চলবে না ফেসবুক, হোয়াটসঅ্যাপ, টিকটক. (2024, July 28). BBC News বাংলা. https://www.bbc.com/bengali/articles/c87rny08e72o

- ডিবি কার্যালয় থেকে সব কর্মসূচি প্রত্যাহারের ঘোষণা ৬ সমন্বয়কের. (2024, July 28). Samakal. https://samakal.com/bangladesh/article/248082/ডিবি-কার্যালয়-থেকে-সব-কর্মসূচি-প্রত্যাহারের-ঘোষণা-৬-সমন্বয়কের

- ঢাকা বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় ক্যাম্পাসে ইন্টারনেট সেবা বন্ধ. (2024, July 15). দেশ রূপান্তর. https://www.deshrupantor.com/523034/%E0%A6%A2%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%95%E0%A6%BE-%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%BF%E0%A6%B6%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%BF%E0%A6%A6%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%AF%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%B2%E0%A7%9F-%E0%A6%95%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%AF%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%AE%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%AA%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%B8%E0%A7%87-%E0%A6%87%E0%A6%A8%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%9F%E0%A6%BE%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%A8%E0%A7%87%E0%A6%9F-%E0%A6%B8%E0%A7%87%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%BE-%E0%A6%AC%E0%A6%A8%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%A7

- ঢাকায় ইন্টারনেট সেবা ‘বিঘ্নিত’, বিটিআরসি বলছে, কোনো নির্দেশনা নেই. (2024, July 17). bdnews24.com. https://bangla.bdnews24.com/bangladesh/0561d9978da2

- প্রতিবেদক. (2024, July 30). শিক্ষার্থীদের সঙ্গে সংহতি জানিয়ে অনেকের ফেসবুক প্রোফাইলে লাল ফ্রেম. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/i75t39xlhp

- প্রতিবেদককালবেলা. (n.d.). সন্ধ্যা থেকেই মোবাইল ইন্টারনেট সেবা বিঘ্ন | কালবেলা. কালবেলা | বাংলা নিউজ পেপার. https://www.kalbela.com/national/105004

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024a, July 16). কোটা আন্দোলন: রংপুরে সংঘর্ষে রোকেয়া বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়ের শিক্ষার্থী নিহত. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/district/2yt74df0iq

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024b, July 17). মোবাইল ইন্টারনেটে ফেসবুক ব্যবহারে সমস্যা. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/h4uzv1zi9f

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024d, July 27). কোটা সংস্কার আন্দোলনকে ঘিরে সংঘাত: নিহত বেড়ে ২১০. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/un7b63tabl

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024e, July 29). কোটা সংস্কার আন্দোলন: সরকারি হিসাবে মৃতের সংখ্যা বেড়ে ১৫০. dhakapost.com. https://www.dhakapost.com/national/295169

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024f, August 1). ছয় সমন্বয়ককে ছেড়ে দিল ডিবি. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/vt91qmdtcb

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024g, August 4). কর্তৃপক্ষের নির্দেশে মোবাইল ইন্টারনেট বন্ধ: অপারেটরদের বিবৃতি. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/hav5wty5j0

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024h, August 4). মোবাইল ইন্টারনেট বন্ধের নির্দেশ. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/5h6t8ay1rl

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024i, August 5). আবার স্বাভাবিক ছন্দে ইন্টারনেট, ব্যবহার করা যাচ্ছে ফেসবুক, হোয়াটসঅ্যাপ, মেসেঞ্জার ও ইনস্টাগ্রাম. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/technology/5lifre3n2o

- প্রতিবেদকনিজস্ব. (2024j, August 15). বিগত সরকারের রাজনৈতিক উদ্দেশ্য পূরণে পলকের নির্দেশে ইন্টারনেট বন্ধ রাখা হতো: বিটিআরসি. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/yhqc15kwke

- প্রতিবেদকবিশেষ. (2024, July 24). কারফিউ আরও শিথিল, অফিস খুলছে আজ. Prothomalo. https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/t37nlcbsc2

- রাজধানীসহ সারা দেশে বিক্ষোভ-অবরোধ: যোগ দিল বেসরকারি বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়ও. (n.d.). Jugantor. https://www.jugantor.com/tp-firstpage/828507

- রিপোর্টস্টার অনলাইন. (2024a, July 17). বৃহস্পতিবার সারা দেশে ‘কমপ্লিট শাটডাউন’ বৈষম্যবিরোধী ছাত্র আন্দোলনের. The Daily Star Bangla. https://bangla.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/quota-protest/news-599271

- রিপোর্টস্টার অনলাইন. (2024b, July 23). কোটা সংস্কার আন্দোলন: ৮ দিনে নিহত অন্তত ১৫০, আহত কয়েক হাজার. The Daily Star Bangla. https://bangla.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news-599696

- রিপোর্টস্টার অনলাইন. (2024c, July 23). কোটা সংস্কার আন্দোলন: ৮ দিনে নিহত অন্তত ১৫০, আহত কয়েক হাজার. The Daily Star Bangla. https://bangla.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news-599696

- সারা দিন বন্ধের পর সন্ধ্যায় সচল ফেসবুক. (n.d.). Jugantor. https://www.jugantor.com/tp-lastpage/833288

- সারা দেশে কারফিউ, সেনা মোতায়েন. (2024, July 20). Kaler Kantho. https://www.kalerkantho.com/print-edition/first-page/2024/07/20/1408230

- বিক্ষোভে পুলিশের বাধা, ধস্তাধস্তি. (2024, August 2). Samakal. https://samakal.com/bangladesh/article/248778/বিক্ষোভে-পুলিশের-বাধা-ধস্তাধস্তি